By Wendy Blake

Two remarkable letters are on display in the New-York Historical Society’s installation “New York Before New York: The Castello Plan of New Amsterdam.”

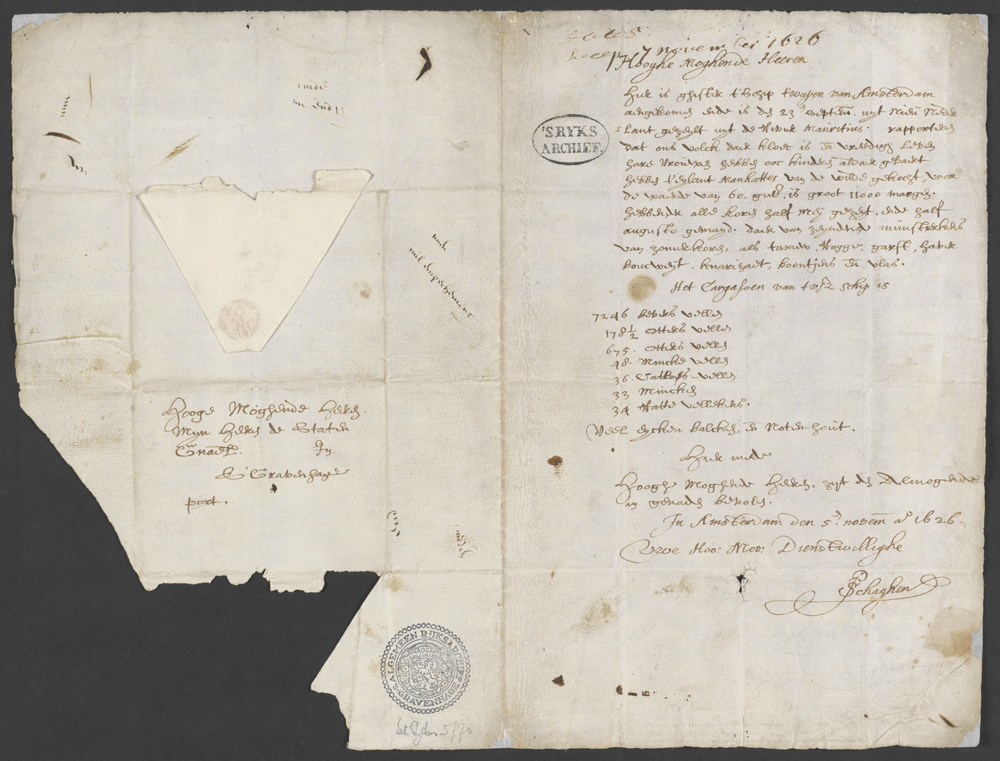

One, a 1626 letter to the Dutch West India Company from an official in New Amsterdam, the seat of colonial government in New Netherland, describes the “purchase” of “the island Manhattes from the Indians for the value of 60 guilders” (converted by a 19th-century historian into $24). That letter is the only record of the infamous transaction.

The second letter, written by present-day Lenape chiefs whose ancestors inhabited the region when the Dutch arrived, declares the “purchase” invalid. Indeed, says Russell Shorto, director of the New Amsterdam Project at NYHS and exhibition curator, who reached out to the tribes for this response, the transaction was a swindle: The Lenape would have viewed the transaction not as a sale but as a land-use treaty, amounting to an economic and defensive alliance with the Dutch. The items valued at 60 guilders (kettles, knives, and such) would not have represented payment for land but gifts typically presented upon the sealing of a treaty.

The chiefs’ letter, addressed to “Ancestor,” decries the 400 years of devastation experienced by the Lenape people but proclaims that the surviving families have reconnected with “the land and waters of Manahahtáanung.”

The NYHS exhibition, which marks the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Dutch settlers, brings together rare items that document the ugly legacies of African enslavement and dispossession of Native tribes while also speaking to the valuable contributions of non-Europeans. It also describes two foundational elements of Dutch culture that positively influenced the city we know today.

“The Dutch brought a tolerance that was unusual in Europe at the time—in fact, intolerance was official policy in France, England and Spain,” said Shorto in an interview with the Rag. “You had this mix of people speaking different languages and worshipping different ways. [The Dutch] showed in effect that tolerance of others was a recipe for economic success.”

As inventors of the stock market, they also imported capitalism. “They were a practical, seafaring people, and it was in their interest to have an entrepôt [a global trading post],” said Shorto. “Everyone in New Amsterdam was a trader. They would put money back into particular ventures and voyages.”

Business in the New World centered on the fur trade—particularly the “soft gold” of beaver pelts, which were secured by Native trappers—paving the way for New York to become a commercial hub. But the city would also become a center of the slave trade.

The earliest known map of New Amsterdam, known as the Castello Plan, is a highlight of the exhibition. Drafted by Jacques Cortelyou, the surveyor general for the Dutch territory in the New World, and illustrated by cartographer Johannes Vingbooms, the map offers a bird’s-eye view of the city at its peak, around 1660. It depicts 300-some houses, home to about 1,500 people; extensive gardens; a windmill; a fort; and a church attended by Christians of many denominations, including enslaved Africans—all south of the fence that would become Wall Street. A 3-D rendering of the map allows visitors to tour the city virtually, taking them down a canal and under bridges.

The map is on loan from the Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy. (It was sold in Amsterdam to Cosimo III de’ Medici, an Italian grand duke, and went missing for over 200 years before turning up in 1900 at the Villa di Castello in Florence; hence the name.)

Though it resembles a small frontier village, the city depicted on the map offered great opportunities for wealth-building, especially for white Europeans. A 1655 book encouraging European emigration to New Netherland (the Dutch-claimed territory that included large parts of the northeast and mid-Atlantic) said the Dutch “regard foreigners virtually as native citizens” and that in the capital, New Amsterdam, “anyone who is prepared to adapt can always get off to a good start.”

But not all were welcomed with open arms. On display is a petition to the city from Asser Levy, one of New Amsterdam’s 24 Jewish residents, who sought burgher status. Peter Stuyvesant, director-general of New Netherland from 1647 to 1664, had barred Jews from being burghers (citizens), which meant they couldn’t serve as guards for the city. Adding insult to injury, Stuyvesant then taxed them for not serving. Levy’s initial petitioning to become a burgher was unsuccessful, but Jews eventually won their case.

The exhibition introduces us to Native figures of the time, such as Seweckenamo, a chief of the Esopus people living north of Manhattan, who in 1664 proposed a treaty to Stuyvesant by carrying a branch to New Amsterdam and promising peace as “solid as a stick.”

It also reveals how Dutch leaders in Europe, appalled by a two-year war between the settlers and the Native population, condemned Stuyvesant’s predecessor, Willem Kieft, for “abominations” against the tribes and recalled him. Kieft had ordered soldiers to massacre Indigenous people in their sleep, sparking a war in which over 1,000 Native people and hundreds of colonists were killed.

Most surviving artifacts from New Amsterdam relate to European settlement, but in 1984, a special group of objects – presumably collected by an enslaved African – was unearthed near present-day Pearl Street. This “mpungu” collection, found buried in a basket covered by a Dutch plate, includes shell fragments, shards of pottery, marbles, and a copper thimble. It was a Central African belief that the objects had to be broken and previously used so that a healer could engage with their energies.

Despite centuries of rapid and unceasing changes on Manhattan island, the original street grid of New Amsterdam remains remarkably intact. But the Dutch colony itself came to a quiet end in 1664, when its citizens surrendered control without resistance to the British. Shorto, whose books include Island at the Center of the World, a history of Dutch Manhattan, says he’ll be writing about the British takeover next.

Wendy Blake, who writes about arts and culture for the Rag, is a descendant of Jacques Cortelyou, the surveyor general of New Netherland who drafted the Castello Plan.

“New York Before New York: The Castello Plan of New Amsterdam” will be at the New-York Historical Society, at Central Park West and 77th Street, until July 14.

Subscribe to West Side Rag’s FREE email newsletter here.

The tolerance of the Dutch in New Netherland has been much exaggerated. They recognized “freedom of conscience,” but prohibited organized worship except in the Reform Church, which was the state religion. Stuyvesant, in fact, wanted to deny residence to Jews, who came to New Netherland after the Dutch were evicted from Brazil. He was overruled by the Dutch West India Company, which had at least one Jewish investor among its governors (the legal status of the Jews in the Netherlands varied by area). Eventually the Jews of New Netherland were permitted to form a congregation—which became Congregation Shearith Israel, located today on West 70th St. Stuyvesant’s antisemitism was not unusual in the Netherlands of that period. He was, in addition, the largest slaveholder in New Netherland (having previously run the West India Company’s slave trading operations in the Caribbean).

I would add that characterizing the Dutch West India Company’s behavior as “capitalism” is simply wrong: it was a colonial enterprise that closely regulated trade and the economic lives of its colonists.

Sounds like we had better look into removing statues and renaming any building that reflects this period in history? How triggering must it be for those who live in the housing development named after Stuyvesant? Even with the rent subsidies? How can we start of petition to make this happen? We can’t allow a legacy of hate, racism, or discrimination in our city.

The Dutch were ahead of their time in regards to tolerance.

Let’s avoid judging a 17th century society by 21st century standards.

I have historical material.

Manhattan wasn’t sold the the Dutch, it was a fishing rights deal, one that expired in 25-30 years.