By Pam Tice

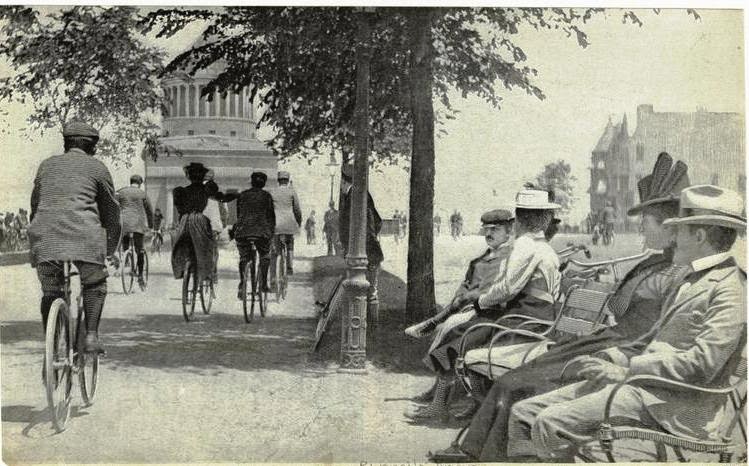

In the 1890s, a bicycling craze swept America as men and women purchased bicycles and took to the roads. The safety bicycle, a machine much like the one we have today with equal-size wheels and inflated tires, fueled the craze as the model became widely available. Bicycles cost from $45 to $75, making the biking craze very much a middle-class phenomenon.

In our Bloomingdale neighborhood (West 96th Street to West 110th Street, between Central Park and the Hudson River) with its paved roadways and two parks, the bicycle craze became part of street life.

Central Park West and Eighth Avenue was paved up to 135th Street by 1898, although riders found the darkened street under the El (running on Eighth Avenue above 110th Street) hard to maneuver. Central Park became popular for bicycling by the mid-1880s, after park rules allowed cyclists to ride on the drives, which were already busy with carriages and horses.

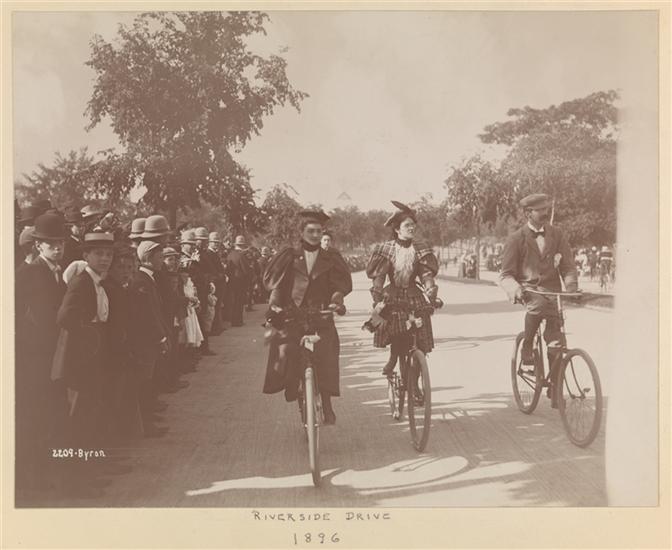

The Boulevard, later named Broadway, was a popular bicycling route, from Columbus Circle up to Grant’s Tomb and the Claremont Inn at West 124th Street. Parts of the new Riverside Drive also attracted wheelmen and wheelwomen, as the bicyclists were called. In the spring of 1896, traffic counters noted more than 14,000 bicyclists over a sixteen-hour period.

As bicycling grew, so did its regulation. Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt initiated bicycle policemen. Traffic rules were passed that classified the bicycle as a vehicle: bicyclists were to stay to the right in traffic, carry a lantern at night, sound a bell when passing or turning, and travel at no more than eight miles an hour.

The bicycle’s popularity spurred manufacturing of special accessories, including clothing for biking. Riding academies opened where novices could learn to ride in inside spaces, and newspapers ran regular columns on bicycling.

Bicycle clubs were popular, at first just for men, and later including a few women; eventually, an all-women’s club formed. One of the most popular was Bloomingdale’s Riverside Wheelmen, headquartered in a brownstone at 232 West 104th Street in 1889. The clubhouse included a billiard room and was the scene of “smokers” and other social activities, like group singing, piano solos, and comic recitations.

The Riverside Wheelmen organized amateur races, subject to the League of American Wheelmen’s rules; for example, if women were allowed to participate, the event would be “unsanctioned.” The club’s races were staged at Manhattan Field at Eighth Avenue and West 155th Street, a popular spot for college football and other sports events.

For non-racing members, the club organized day-long rides on weekends up to Westchester County, over to New Jersey, or through Brooklyn to the Rockaways, where participants could go swimming.

One of the first captains of the Riverside Wheelmen was Franklin M. Cossitt. In 1887 he married Caroline Gray; “Carrie” joined him in his bicycling enthusiasm, and in some news reports she is referred to as a member of the Riverside Wheelmen. An 1890 city directory lists their home as West 119th Street. Carrie signed up for a century (100-mile) ride in Philadelphia in 1890, but the poor condition of the roads exhausted her and she could not finish, the only time she tried an event she could not complete.

Another woman who was sometimes referred to as a Riverside Wheelmen member was Nellie Benson. She lived on West 65th Street and rode tandem with Fred Lester who lived at the same address, although she was always referred to with a “Miss” before her name. In 1897, Fred and Nellie rode from City Hall in New York to City Hall in Philadelphia, with Nellie in front. In 1896, Fred and Nellie were arrested for “scorching” (riding fast) on the Boulevard; when they were brought into court, the judge found that he could not fine “a lady” and so Fred had to pay the $3 penalty twice.

In 1891, James Powers, a comedic actor and singer who lived at the Ansonia, applied for membership in the Riverside Wheelmen. The announcement of his application noted that many artists and writers were attracted to that club.

As bicycling’s popularity grew, religious leaders across the country expressed concern that it was keeping young people from church on Sundays. Church attendance by men had already fallen off, and now ministers worried that women would stop coming to services.

The Reverend John Peters of Bloomingdale’s St. Michael’s Episcopal Church (Tenth Avenue at West 99th Street) had an idea. In June of 1896, he arranged for the church to set up a “bicycle check-in,” encouraging people to attend the 7:30 am service before setting off for their Sunday ride. His wife, in a New York Times interview, expressed sympathy for working people whose only day off was Sunday, noting that late-morning services interfered with having the whole day for restorative recreation. The church placed a sign in the drugstore a block away and planned further signage to attract the bicyclists riding uptown to stop by St. Michael’s for the early service.

The city’s bicycle clubs all had uniforms, so when they rode together, they would be recognized. By mid-decade, bicycle parades were popular. A June 1896 event sponsored by the Evening Telegram brought crowds to the westside. Costumed riders headed uptown on the Boulevard at West 66th Street, riding up to West 108th Street, crossing over to Riverside Drive, then up to Claremont Avenue, and back downtown. Riders were given awards for having the most grace, best costume, and best club.

Criticism of women bicycle riders was tremendous. There were claims that a woman getting on a bicycle might cause sexual arousal and predictions that bicycling would render women infertile. Some said bicycling made a woman’s hands become enlarged, caused a loss of femininity, and would lead to women becoming more like men. Bicycling also challenged the social norms which constricted women from meeting men only under the supervision of their parents.

Those in favor of bicycling for women presented the healthy outcomes that would result: the improvement of muscles and overall well-being, the opportunity to explore the world and learn about history and geography, and the freedom to move around without having to ask someone’s help. Susan B. Anthony said, “I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

One of the most popular topics in the press about wheelwomen involved proper clothing. Bloomers had a mixed history from an earlier attempt to make women’s clothing more rational. During the bicycle craze, the city’s tailors worked to develop comfortable riding costumes. The choice that became the most acceptable was knickers with a shorter skirt over them, stockings, ankle boots, a short jacket, and a not-too-big hat. Some women, like century-rider Nellie Benson, wore just knickerbockers with no skirt.

Marie Ward, of the Ward’s Island New York family, known as “Violet,” included all of the best clothing choices in her popular book Bicycling for Ladies. She ran a bicycle shop on Staten Island, and her book included information on bicycle repair and the tools needed, reminding women that they already used needles and scissors and so could easily adapt to bicycle tools.

One measure of the ending of the bicycle craze was the fall-off in League of American Wheelmen membership, which dropped from over 100,000 in 1898 to just 8,600 in 1902. The craze was over. Bicycling returned somewhat during the Depression, but by the 1940s and 1950s bicycles were considered children’s toys.

Pam Tice is a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group and has served as executive director of Bike New York.

Subscribe to West Side Rag’s FREE email newsletter here.

In more recent history, Central Park had marked dedicated bike paths. You can still see the curb divider between pedestrian path and bike path by the Sheep Meadow near Tavern On The Green. Before fax machines and email there were also many many bike riders doing messenger work. They expertly weaved among the cars and traffic requiring no special lanes and were not nearly the menace to pedestrians that bikes are today.

I think the separation near the Tavern On The Green was the bridle path, used by the “horsey set”.

Most important fact about bike riding in NYC in the 19890’s – there were hardly any automobiles. Horses were the mode of transport.

I think they were created for horse carriages, not bikes. Not many will agree with you that bike messengers didn’t pose a threat to pedestrians and cars in their heyday.

completely charming history; thank you! I knew about the bicycle craze, but many of these details were new to me.

“14,000 bicyclists over a sixteen-hour period”!! That should deflate the commenters who feel we are overrun by bikes today (while also somehow pointing to the perceived scarcity of bikes to justify anti-bike-lane sentiment).

But you didn’t mention Police Commissioner Teddy Roosevelt’s regulation of bicycles. Don’t see any enforcement by today’s police cracking down on bikes going the wrong way on one way streets or riding on the sidewalk. Tell me you don’t have to look both ways before crossing the street or looking out for bikes running red lights…

Messenger bikes were not viewed as a menace 40 years ago. I did not walk around the streets constantly looking out for them- today is very different – they have become a menace and looking out for them at all times is now a necessity.

A limit of 8 miles per hour sounds like a good start for e-bikes and their drivers.

What a wonderfully detailed piece of history, including Susan B. Anthony’s “standing and rejoicing” every time she saw a woman on wheels. I am sharing with all my neighbors and neighborhood friends.

Love this article. It’s great to read about the history of the city and UWS.

Just where they belong in the 19th century.

I loved this piece.

As my wife and I coast through Riverside Park at a leisurely pace, we will make sure to tip our proverbial hats to the wheelmen and wheelwomen of yesteryear as we look out for scorchers from past and present. I’m afraid we won’t win any prizes for costume or grace in the parade…

As someone who grew up on the UWS riding a bicycle during the 50’s, I think the statement that bicycles were just considered children’s toys is completely inaccurate.

As a teenager in the 50’sI rode my bike all over Manhattan. In summer camp we had bicycle excursions. In college the bike was an essential means of transportation to classes.

I don’t recall anyone thinking of a bicycle as a “toy” .

The author mentions affordable bikes at $45-75. Using the Consumer Price Index inflation calculator for 1913, earliest year avaiable, A $60 bike would cost about $1900 today. Seems a little steep for most people.

$45 to $75 in 1890 would be $1,535 to $2,558 today. Is that a middle class price range?

LOVE this article. Thank you so much for all the research and for writing it and posting it!

A delightful article. Why did the craze happen so suddenly?

It’s nice to know bike history in nyc but nothing will take away the facts of todays

bike phenomenon. It’s has made our streets

unsafe not enough room in streets AND for

traffic

Most to facilitate delivery

What’s more important?

Safe streets or delivery bikes

All electric bikes must be removed

Remove all bikes

Return to safe streets