By Bonnie Eissner

Beware. A visit to Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School, a new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, may prompt a trip to Niagara Falls or the Great Smoky Mountains. That’s because WalkingStick paints these and other landscapes with a sensuousness and a deceptive simplicity that whet the appetite for nature.

At the same time, WalkingStick, a member of the Cherokee Nation whose father was Native American, shows in many of her paintings, especially her recent ones, that America’s natural wonders, from the rocky New England coastline to the jagged Rocky Mountains, are not the sole property of the European settlers who have claimed them. Rather, they are the land of the Native Americans from whom the land was stolen.

The show, with about 40 works, is the largest-ever New York museum exhibition of art by WalkingStick, who is 88. It intersperses her works with paintings from the museum’s substantial collection of Hudson River School art, including works by Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, Asher B. Durand, John Frederick Kensett, and Jesse Talbot. The idea is to create a visual dialogue between the two approaches to landscape. The exhibition invites viewers to see the complements and the contrasts between WalkingStick’s works and those of the New York-based artists who created the American landscape tradition.

WalkingStick first approached landscape painting in the mid-1980s after a period of painting abstract works, such as her Chief Joseph series. The first room of the three-room exhibition shows some of her abstractions as preludes to her more representational landscapes. Two of them, Montauk and Satyr’s Garden, are large, square, densely textured, minimalist works that refer to real or imagined places. In Montauk, WalkingStick evokes the sensation of the beaches at the eastern end of Long Island with roughly 30 layers of tan, green, and pink paint embedded with beach pebbles.

Abstraction has informed WalkingStick’s approach to landscape even as she has moved into more representative paintings, including her signature diptychs.

The exhibition features several diptychs, such as July Low Water, which offers reflected images of the same Ramapo River scene. In some of her diptychs, WalkingStick mixes pure abstraction with representation, creating a conversation between a painting that is time-bound and one that is timeless.

There is also the lively conversation between WalkingStick and the Hudson River School artists. In the first room, Catskill Study, a lush and richly detailed painting by Durand of a rock-strewn mountain stream and its densely forested shore, hangs next to a black-and-white ink painting by WalkingStick of Vermont’s Gihon River. WalkingStick’s undulating lines and jazzy composition convey an impression of fast-moving, even chaotic water, while Durand seeks an authentic rendering of a pristine landscape. Both artists display a reverence for nature but different approaches to conveying its beauty and wildness.

Contrasts between WalkingStick and the 19th-century painters heighten in the second room of the show. WalkingStick’s portrayals of mountainous landscapes, mostly in the West, are pitted against Hudson River School depictions of the West as a place of near mythic beauty and vastness, ready for settlement. In a poignant pairing, Walkingstick’s Farewell to the Smokies (Trail of Tears) hangs next to two paintings by Bierstadt from his travels west — a portrait of Native Americans and a landscape. The portraits are sensitive, and the landscape, with Native Americans in it, is cinematic. Bierstadt was inviting Easterners to the West, and, as he wrote, he believed that the Indians would “soon be known only in history.” In WalkingStick’s painting, two mountain peaks rise in brown and green over small specters of her ancestors, hunched and burdened, who walk west in a line across the foreground.

In portions of her recent landscapes, WalkingSick overlays Native American patterns. The geometric designs, which float above the scene, are intended to serve as a barrier guarding the landscape, WalkingStick says in an interview with the show’s curator Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto in the accompanying catalogue.

WalkingStick began with the designs of parfleche, or painted rawhide bags historically made by women of Western Plateau, Great Basin, Transmontane, and Plains migratory cultures for seasonal travel. These parfleche designs are prominent in two paintings of the Bitterroot Mountains evocatively titled Our Land. Nez Perce Chief Joseph led his people over those mountains in an ill-fated attempt to avoid capture by U.S. Army in 1877.

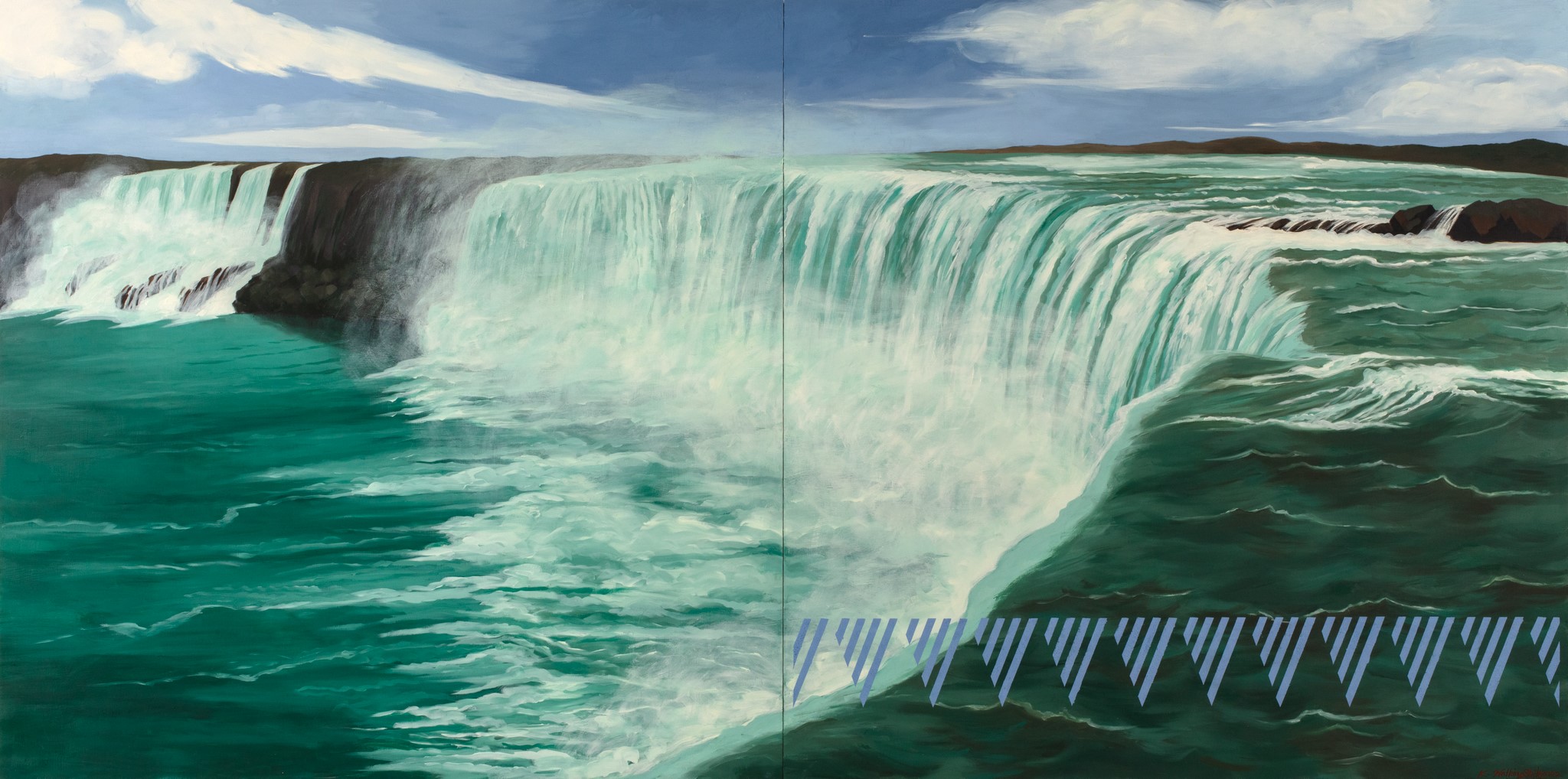

The show culminates with WalkingStick’s more recent paintings inspired by the New England coastline, each showing the pattern of a local Native American tribe, and her monumental 2022 painting Niagara, which anchors and helped inspire the show. It is also the first painting by a Native American artist to join the museum’s permanent collection.

Flanking Niagara are two smaller paintings of the falls from 1818, both titled Niagara Falls, by Louisa Davis Minot, one of few women landscape painters of the age. Minot’s works capture the sublime setting, the rushing water and the billowing foam. One can almost hear and feel the thunderous roar. The falls’ great height is evident from the small figures that dot the foreground, including, in one, some stereotypical Native Americans. Seeing the paintings in the museum’s storage facility last year inspired WalkingStick to visit the falls and to paint them.

Walkingstick’s painting, which she described in a talk at the show’s opening as a picture of “my falls,” depicts a top-down view of the falls in, as she termed it, veridian green, white, and the dark brown of the rocks. On the lower right side of her work, like a row of flags, she has painted a band of triangles inspired by the designs on a Haudenosaunee stoneware jar, which, fittingly, is on display nearby. The message WalkingStick intends to send, she said, is, stop and look at this before you see the rest of the painting.

“I hope that a work like this,” Ikemoto said of Niagara, “will disrupt the perception that American art is the art of the settler.”

To receive WSR’s free email newsletter, click here.

Very cool. The N-YHS has been firing on all cylinders lately, many quality shows…will definitely check this one out!

Looks like a beautiful exhibit. Thanks for the info.