By Anya Schiffrin

When I was growing up, a fixture in my mother’s life was her monthly lunch with her Upper West Side women friends whom she gathered with to discuss their lives. They were young mothers, adjusting to New York City. The women took turns hosting each other in their Upper West Side apartments — mostly between West 90th and 106th Streets. They had jobs and children and plenty of activities, but ladies’ lunch was central to their lives and happiness. Kids were not allowed to attend and, of course, husbands (in absentia) were often dissected.

It was the era of second-wave feminism, coinciding with the civil-rights and anti-war movements. Starting in the late 1960s (no one can remember the date), my mother (or whomever’s turn it was) would cook some dish of the era, like gazpacho or Moroccan chicken with olives and lemons, and they would settle into a long afternoon discussing topics such as “does having small children make you hate your husband?” or “if you had to do it again what would you do differently?” They talked about their childhoods, the differences in the schooling they received, the pros and cons of marriage.

An excerpt from a 1999 letter by my mother describing a lunch:

“Another conversation we had was inspired by an article Janet Burroway wrote about how her generation at Barnard and Sylvia Plath were driven to divorce, drink and suicide by pressures to get married and once married to serve their husbands rather than their careers. Stella and I felt that the pressures to get married were internal. Sheila said she felt no pressure. Apart from that we talked about whether you can have a happy life, staying at home and looking after your parents.”

Part of why ladies’ lunch was so important is that several in the group were New York transplants and some had been refugees. The ones who grew up in England idolized English life and couldn’t quite believe they had landed in America. They loved comparing London to New York and discussing what was better/worse about each place (better conversation in London, higher standard of living in New York).

Today, aging has snuck into their conversations, along with bossy daughters, but never grandchildren — and they remain true to talking about their lives. The oldest is 94 and the others are in their late 80s. They’re mostly still on the Upper West Side and still meet.

My mother Maria Elena, whom everyone calls Leina, was born in Spain and exiled during the Spanish Civil War, moving to England with her parents in 1939, and then to New York in 1960 to marry my father, André Schiffrin, who went on to become an influential publisher. They met when they were both studying at Cambridge in the 1950s.

Others in the lunch group who had lived in England included: Inea Bushnaq, who moved to New York and married CUNY professor Robert Engler; and Deirdre Wulf, who married the American Civil Liberty Union’s legal director, Mel Wulf. Member Sheila Greenwald, the children’s book writer, was married to the heart surgeon George Green. Anna Lou Aldrich, who emigrated to New York in 1940, lived in 11A in our building and had been married first to “Doc” Humes and then to the writer Nelson Aldrich Jr.

Wulf remembers that in the tumultuous times of the 1970s, the lunches were a “cocoon.” “Leina all but banned politics as a topic, and we were happy to go along with her preference,” she said. As my mother puts it: “The reason I didn’t like talking politics in these sessions is that I had plenty of people I talked politics with, but few in New York to talk about Life with.”

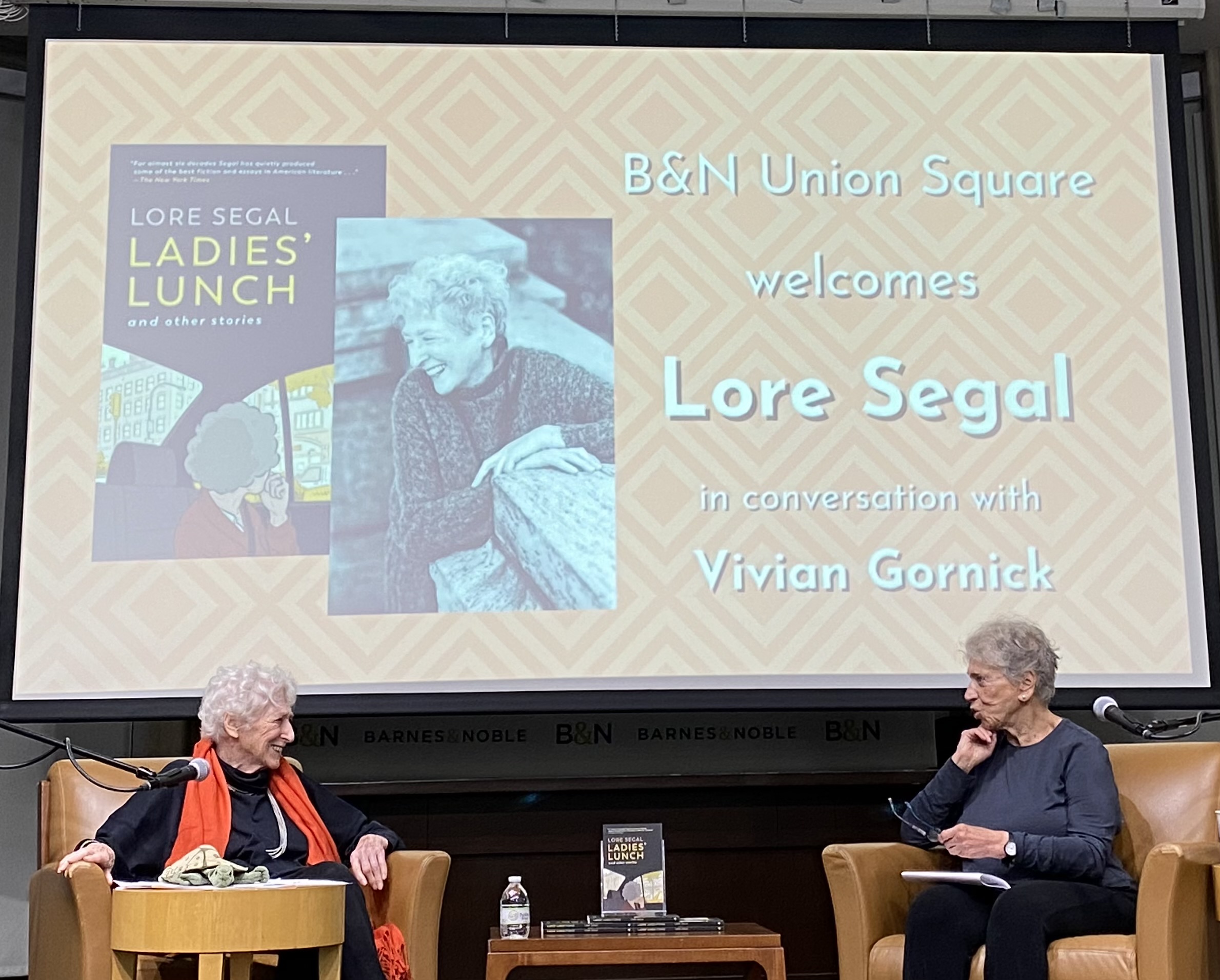

Lore Segal, the novelist, was one of the early members of the group, and last month a collection of her short stories, Ladies’ Lunch, which appeared in England in 2022, was published here. The stories purport to be about the group but everyone else in the group says they are nothing like what really happened. “It’s fiction based on her experience, like most of her writing,” Lore’s daughter told me in an email, after consulting with her mother.

In “Ladies Lunch,” Segal’s character is Ilka Weisnix, described in the book as having “the twenty-year-old European’s simple-minded superiority to all things American.” In real life, Segal left Vienna on the Kindertransport in 1938, and spent 10 years with different foster families in England (her book about this experience is Other People’s Houses ). She was eventually reunited with her parents and the family moved to the Dominican Republic and then to Washington Heights in New York City. Segal dated a sociologist/writer whom she fictionalized as Carter Bayoux in the novel, Her First American, which is really about Black-Jewish relations in the 1950s. She published fiction and essays in The New Yorker for many years (and still does).

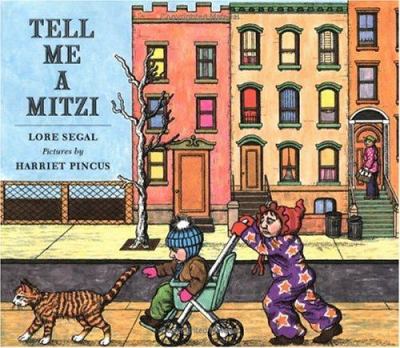

As a child, one of my favorite “Lore books” was the Mitzi children’s book series. Illustrated by Harriet Pincus, Tell Me a Mitzi is about two children, based on Segal’s kids, having adventures on the Upper West Side — including sneaking out in the early morning, hailing a cab, and visiting their grandparents who lived opposite the Natural History Museum on 77th Street.

As a child, one of my favorite “Lore books” was the Mitzi children’s book series. Illustrated by Harriet Pincus, Tell Me a Mitzi is about two children, based on Segal’s kids, having adventures on the Upper West Side — including sneaking out in the early morning, hailing a cab, and visiting their grandparents who lived opposite the Natural History Museum on 77th Street.

Through her books, Segal’s readers can follow her life. Her latest is about the indignities of aging: weakening memory and sight, losing (or arguing with) old friends, falling, the arrival of aides, the death of husbands. In one story, the ladies plan a trip to a retirement home to visit one of their own who has been “put away” in the country by sons with the best of intentions — but, also, at the end of their ropes. As the story comes to an inevitable conclusion, there are no villians here.

Over the years, the real ladies’ lunch evolved. New friends were added. Anna Lou Aldrich died, though her daughters are still friendly with all of us. Even I was allowed a couple of times to host lunches where daughters were invited, including the Aldrich daughters (though the ladies probably never quite enjoyed that as much as being without us). At some point ladies’ lunch morphed into Wednesday Tea & Tipples—beginning with tea at 4 p.m. (less work than cooking lunch), and then at 6 p.m., the whiskey bottle was brought out and the tippling began. During the pandemic, ladies’ lunch was held on Zoom.

When I can, I go and see them. I often ask them for advice about my life because they are frank and funny and wise and their memories are far better than they think.

To receive WSR’s free email newsletter, click here.

A lovely article. Having many friends who are women in their 30s to 50s, most of whom have mothers still living, I had to chuckle over “bossy daughters.”

LOL. Needless to say we daughters don’t think we’re bossy. We view ourselves as saintly and brimming with brilliant ideas if only our mothers would listen to us!

I have long admired the brilliant, no-nonsense older women of the UWS. You know what they think, they have much to teach, they will tell you to go to hell if you’re being a jerk, and then they will invite you to tea or lunch as if nothing ever happened.

I had such envy reading about your mom’s lunch group. I moved to the UWS three years ago, having grown up in the Bronx, gotten married at 21, and spending the next 57 years in the suburbs. Now at 81, I have friends I see, but would love to be part of an intimate group like that (without making lunch!) where I could let down what’s left of my hair, and most certainly without the bossy daughters!

Thank you very much. Can you organize a group? Maybe just tea & T ?

Is it possible the “bossy daughters” learned that lesson from their mothers? 😉

Lol! Next time you run into my mother at fairway, please ask her

Loved reading this article. What an interesting group of women. I’m sure they loved those lunches and conversation.

I too long for such a group. Is it too late to build upon the old or start a new? The issues are different, but the perspectives are the same. How I miss the chance to be with my “sisters”.

DEFINITELY not too late. I have just started another group in England where I now spend part of my time.

Everyone in the comments is being so lovely. Maybe you need to get together and start a new group (or am I being bossy for suggesting this?)

I was so happy to read Lore Segal’s recent piece in the New Yorker. I too was on a Kindertransport to England, and a piece of hers in the New Yorker was my first realization that I had been part of something larger than my own train journey.

Does anyone still wear a hat?

Once long ago, ie, the early 1970’s, a woman in my building posted a not in the lobby asking if anyone would like to join a Women’s discussion group. 25 off us did, and we met one evening a week for almost three years. A daughter at college in the late ’80’s gasped “you did? ” from a history class of American women.

I loved this article and it made me especially happy to see Lore Segal as a member of this group, which is the same kind of gathering my mother has had with friends (all now in their 80’s). Lore Segal’s book “Other People’s Houses” is brilliant and even though I never experienced all that she went through, still managed to connect by also just being about a girl coming of age. I would love to convey to her how much that book meant to me (and that I just gave it to an Afghan refugee friend as well.) Thank you

This is so great