By Wendy Blake

A new exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, “Sightlines on Peace, Power & Prestige: Metal Arts in Africa,” showcases 140 stunning artifacts — mostly from the 18th to early 20th centuries — alongside contemporary work by artists from Africa and the African diaspora. In sparking “conversations” among these objects and their creators, the show aims to forge lines of connection from the past to the present.

“The histories of displacement and dispossession under which these metalworks have lived mean that many of their stories are beyond reach,” says curator Drew Thompson, associate professor at the BGC. “What do you do in that absence?”

That question drives modifications Bard has made to the original show, which was curated at the Harn Museum in Gainesville, Florida. Instead of grouping the metalwork by era or material, the Bard gallery has arranged the pieces thematically, allowing for fresh associations. Bard also added the contemporary work, created by 13 world-renowned artists. These changes contextualize the objects and invite us to re-imagine their stories— the people who made them, who used them, and from whom they were separated, as well as the ways in which they “circulate in memories and in people’s hands,” says Thompson.

The focus on the hows and whys of exhibition design makes sense, since the West 86th Street townhouse gallery is connected to the BGC, which prepares students for careers in academia, museums, and the private sector. A group of students was present when I visited, discussing how the layout prompted different interpretations. BGC, affiliated with Bard College, was started in 1993 by art historian Susan Weber, with the goal of understanding the past through objects—those created for aesthetic value as well as everyday things.

Thompson, the curator, made another change to the Florida show in order to bring attention to the devastating effects of colonialism, excluding five objects that were in the original show and replacing them with empty pedestals. They were among the “Benin Bronzes” looted during the savage British occupation of the West African kingdom of Benin, which led to thousands of items being scattered worldwide in institutions and in private hands. Thompson notes, “As curators, we have a role in opening up debates.”

The exhibition’s first room, titled “Extraction,” investigates colonial resource exploitation and the enslavement of skilled metalsmiths, some of whose traditions dated to the 6th century. “Double Plot” (2018), a tapestry by Nigerian-Belgian artist Otobong Nkanga, depicts silver lines resembling veins of ore, scarified land, borders, and constellations against a backdrop of the solar system. A headless figure manipulates a copper thread, which passes through grasping hands and planet-like circles bearing images of protest. The work speaks to Nkanga’s ideas of how exploitation of the earth disrupts systems that allow for restoration and regeneration.

Here are brass weights that were used by the Akan people, who once controlled the gold trade in West Africa, to measure gold dust. Even the tiniest weight has a story: One from the period of British colonization of what is present-day Ghana is shaped like a royal seat but was modeled after folding chairs used by European settlers. The show also makes the point that “extraction” is not unidirectional, as seen in a Teke ceremonial ax studded with brass tacks imported to Africa from Europe.

The “Devotion” room includes a striking 19th-century brass-and-copper reliquary guardian figure from Gabon, designed to “bring the power of the dead to life,” says Thompson. An audio feature draws a “sightline” between the figure and a chilling installation—“Swing Low” (2015) by Nari Ward, a Jamaican-born New York artist. A tire cast in bronze hangs by a thick rope—both a child’s swing and a symbol of lynching. Sneakers—“relics” of Black men brutally murdered—burst through the tire, their bronzed tips offering the possibility of traction and movement.

The “Protection” section features a monument to victims of forced migration: “Senait & Nahom. The Peacemaker & The Comforter” (2019) by Tsedaye Makonnen, the daughter of Ethiopian refugees. Light shines from within a tower, through cutouts of Ethiopian Coptic crosses, memorializing a 19-year-old Eritrean woman who killed her baby and herself in an asylum center. Nearby is a rare silver “pectoral cross” from the late 15th century, possibly Ethiopian, with an image of Mary and the infant Jesus—it would have been worn for protection.

Key stories would go untold if aesthetics were the only lens with which to view these objects. Platter-sized brass anklets worn by unmarried Igbo girls and women at the turn of the 19th century hobbled their wearers and could even affect their development. Contrast these with elaborate jewelry from the goldsmithing workshop of celebrated Senegalese designer Oumou Sy. Wearing such bling embodies a Wolof tradition called sañse, defined by Sy as “to dare, to present yourself in your finest — without fear.”

The idea of erasure is in the many bells on display, objects used to summon ancestors and spirits. Encountering an ancient bell with enigmatic human face intact but clapper missing, we’re encouraged to imagine a rich soundscape and rituals that, without documentation, are lost to us.

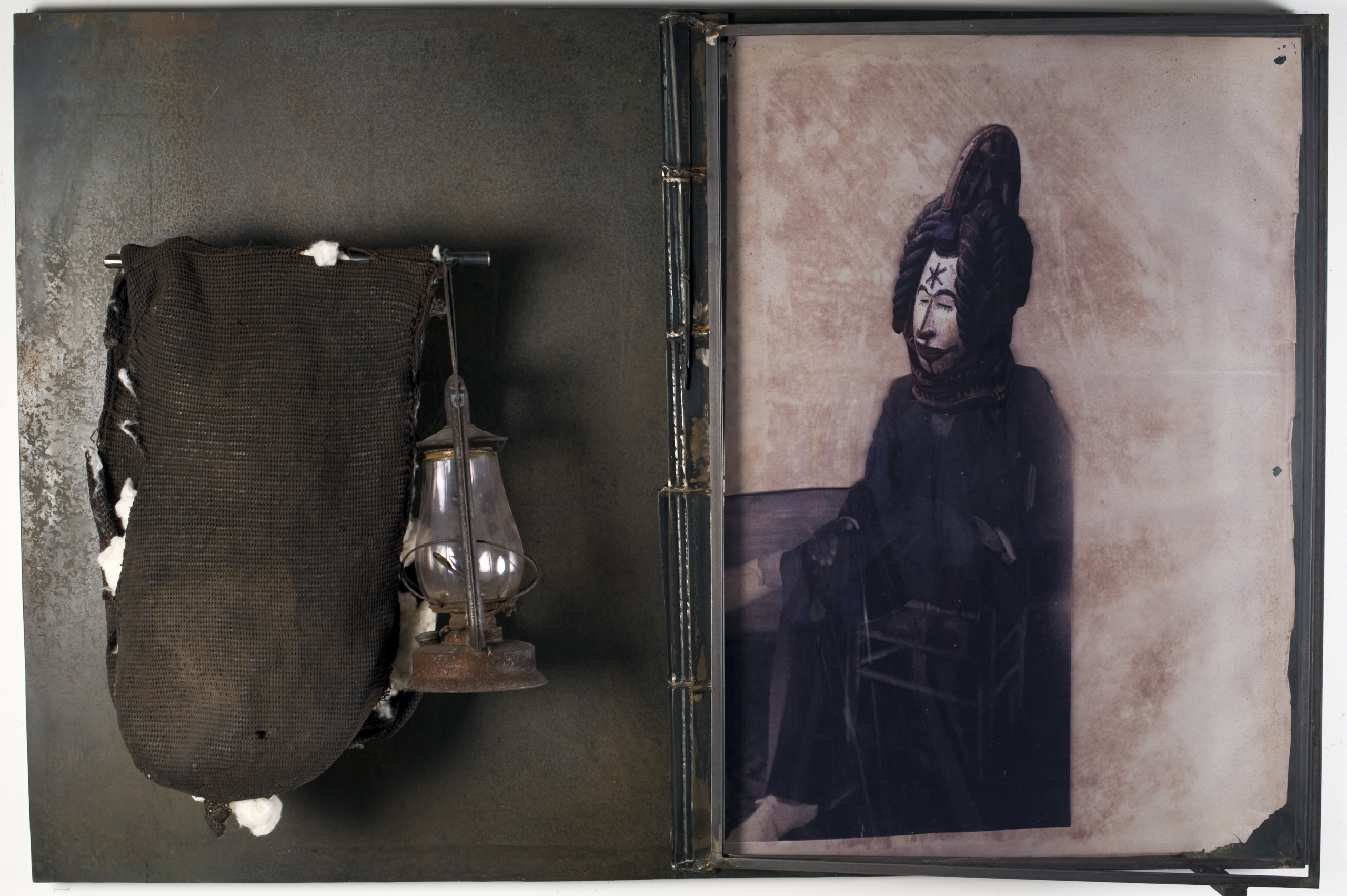

Meanwhile, Radcliffe Bailey’s “Ebo’s Landing” (2013) speaks to the power of memory-making and storytelling to re-animate history. This assemblage of objects—including a lantern, a bag of cotton, and a family photograph—evokes his ancestors’ journey north via the Underground Railroad. The title references an 1803 event in which Igbo captives in Georgia rebelled and then drowned themselves to escape their fate. As it was passed down orally, it became a mythic tale of resistance; in one variation, the captives assume magical powers, becoming birds and flying to freedom.

“Sightlines on Peace, Power & Prestige: Metal Arts in Africa” will be at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, 18 W. 86th St., until Dec. 31, 2023. Hours: Tues., 11 am–5 pm, Wed., 11 am–8 pm, and Thurs.–Sun. 11 am–5 pm. Admission is $15, but is free all day on the first Friday of each month, when gallery hours are extended until 8pm.

To receive WSR’s free email newsletter, click here.

Beautiful and haunting and spiritual. Can hardly wait to go!

Beautiful !

Is there an entry fee?

We’ve posted all the details above. Thanks!

Great article and some great photos (can we get photo credits). Did they have the Benin bronzes and didn’t show it? I had gone to the exhibit but feel like I learned more from this article. Nice to see art featured

So glad you liked the article ! Thank you for your kind words.

All photographs of the metalwork were taken by Vincent Girier Dufournier.

All the photographs of the installations were taken by Da Ping Luo.

I just now that the bronzes were in the original exhibition, which was curated at the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida, and that BGC chose not to present them. Two of the objects—a ceremonial sword and a scepter—belong to the Harn Museum, and the rest are in private collections.

Nice. Are metalworks underrepresented in African art exhibits?

I understand that they are — generally, exhibitions tend to focus on sculpture and masks.

Saw this exhibit today – Oct 19 – it is fantastic, and fantastically beautiful. Takes up four floors. Was more attuned to the extraordinary older pieces, tho the contemporary pieces were moving as well. Wow. This merits a big review from the NYTimes – why aren’t they there ?