By Alex Maroño Porto

Columbia University graduate student Inci Sayki grew up in Turkey, a country at the intersection of the Anatolian, Arabian and African tectonic plates. Earthquake safety drills were a regular part of her school curriculum. So when her mother called from New Jersey a little after 8 p.m. on Sunday, February 5, sounding concerned about reports of an earthquake in southern Turkey, Sayki wasn’t particularly alarmed at first. “I didn’t really think that it’d be that big,” she said in a phone interview. But as she learned the next morning, this time was different.

The first shock, near Gaziantep in southeast Turkey, measured 7.8 on the earthquake magnitude scale, releasing an energy capable of powering New York City for over four days. Dozens of aftershocks followed, including a 7.5 magnitude quake close to the city of Elbistan, approximately 70 miles north of the first tremor. With more than 40,000 people killed in Turkey and neighboring Syria, the earthquake is one of the deadliest in decades, reducing historic cities like Antakya to rubble.

While the tragedy has dominated headlines for days, it hit particularly close to home in one corner of the Upper West Side: Columbia University, where more than 100 Turkish students and several Syrians are currently enrolled, according to Samantha Slater, Columbia University’s director of media relations.

Once Sayki grasped the gravity of the catastrophe, she called her maternal grandmother, who now lives in Istanbul but is from Kahramanmaraş, a city many residents call Marash, next to the earthquake’s epicenter. Their family house in Trabzon Street, in the city center, had been fully demolished, Sayki learned, and several cousins who were living in that area perished after they were trapped by collapsed buildings. “It is a collective trauma,” Sayki said.

For the next few days Sayki was glued to Twitter, reading desperate pleas for help. Paralyzed by the tragedy, she went to New Jersey, where her mother and some of her Turkish relatives live, and where she could find company in her grief. “I was able to come here and share that with people in my community who would be able to relate,” she said. “Everything else seemed so unimportant to me, I couldn’t focus on anything.”

The same was true for Abdullah Ayasun, another graduate student from Istanbul who is studying journalism at Columbia. Ayasun skipped his Monday classes, spending the day checking on friends and family while looking at the #deprem (earthquake) posts on Twitter. “I wasn’t able to sleep, because I was scrolling,” he said in a phone interview.

As more information came out, it became clear that unregulated construction and political corruption had contributed to the horrific death toll. “More people could have been saved if they acted early,” said Ayasun. “The public anger is unprecedented,”

Columbia President Lee Bollinger issued a statement of condolence, noting that Columbia has students, faculty, and staff who come from the earthquake region, and one of the university’s several Global Centers is in Istanbul. The university has announced that at least two of its graduates died in the earthquake. On campus, a vigil was organized last week, where Ayasun and other Turkish students could come together, sharing their grief for the lives lost thousands of miles away from Morningside Heights. “Nobody can alone handle this painful process,” said Ayasun. “So I try to spend time together with other friends who are affected by this same trauma.”

Columbia’s Turkish community was also a lifeline for Yasemin Aykan, a master’s student in the department of Art History & Archaeology who received her bachelor’s degree at Barnard College in 2021. Aykan learned about the earthquake on Sunday night through Instagram, but she didn’t fully understand the scale of the event until the next morning. At first, she thought social media was exaggerating, but once she contacted her parents in Istanbul, reality hit.

“They’re like, ‘this is one of the most catastrophic events of the century’,” Aykan said in a phone interview with the Rag. Although she didn’t have any close relatives in the earthquake area, a close friend soon told her about an aunt trapped in a city close to the epicenter. “She’s under the rubble, they still cannot reach her,” Aykan said on Saturday evening. “What I’m saying to my friend is try to be hopeful. A lot of people are still being rescued, so she might be sleeping.”

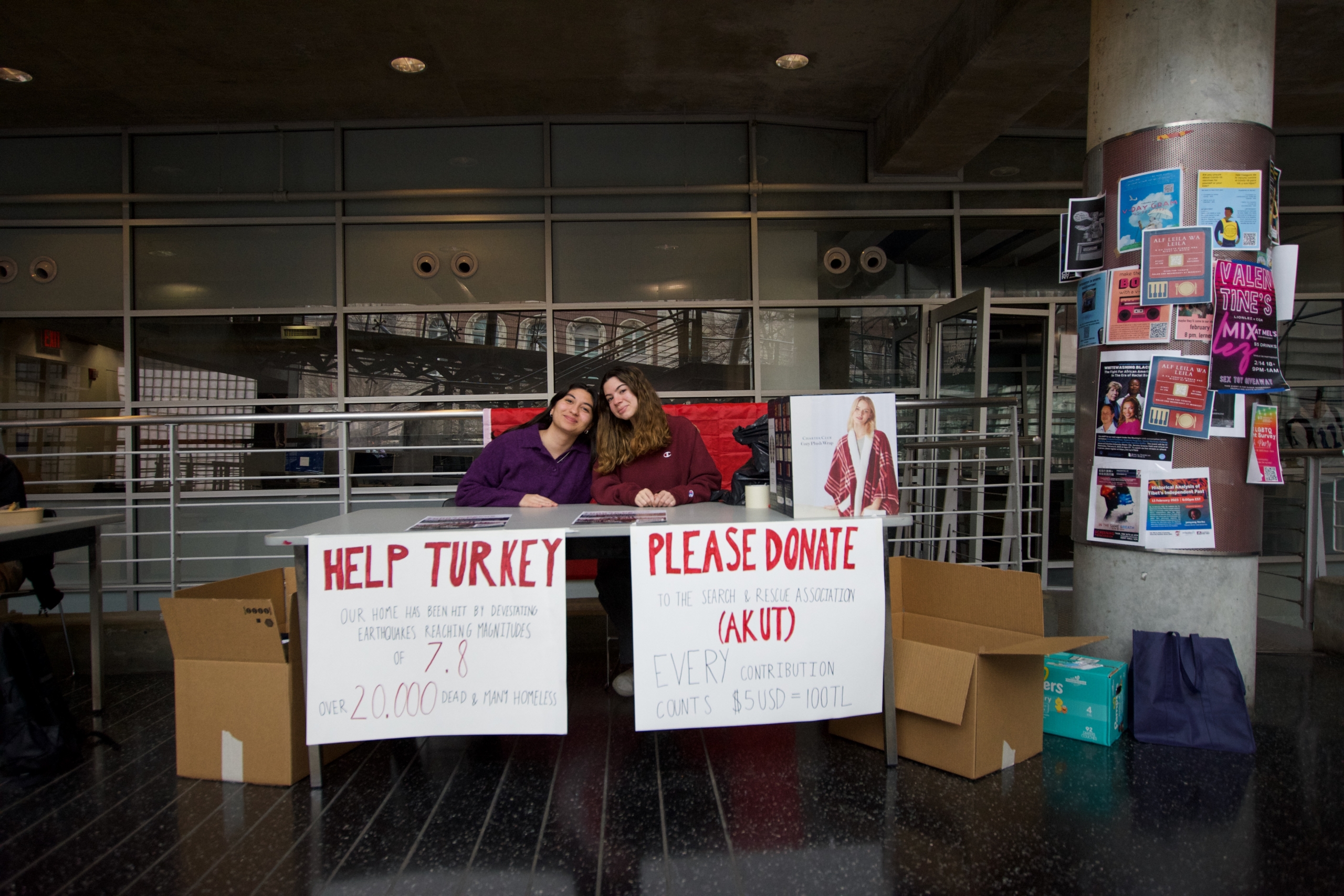

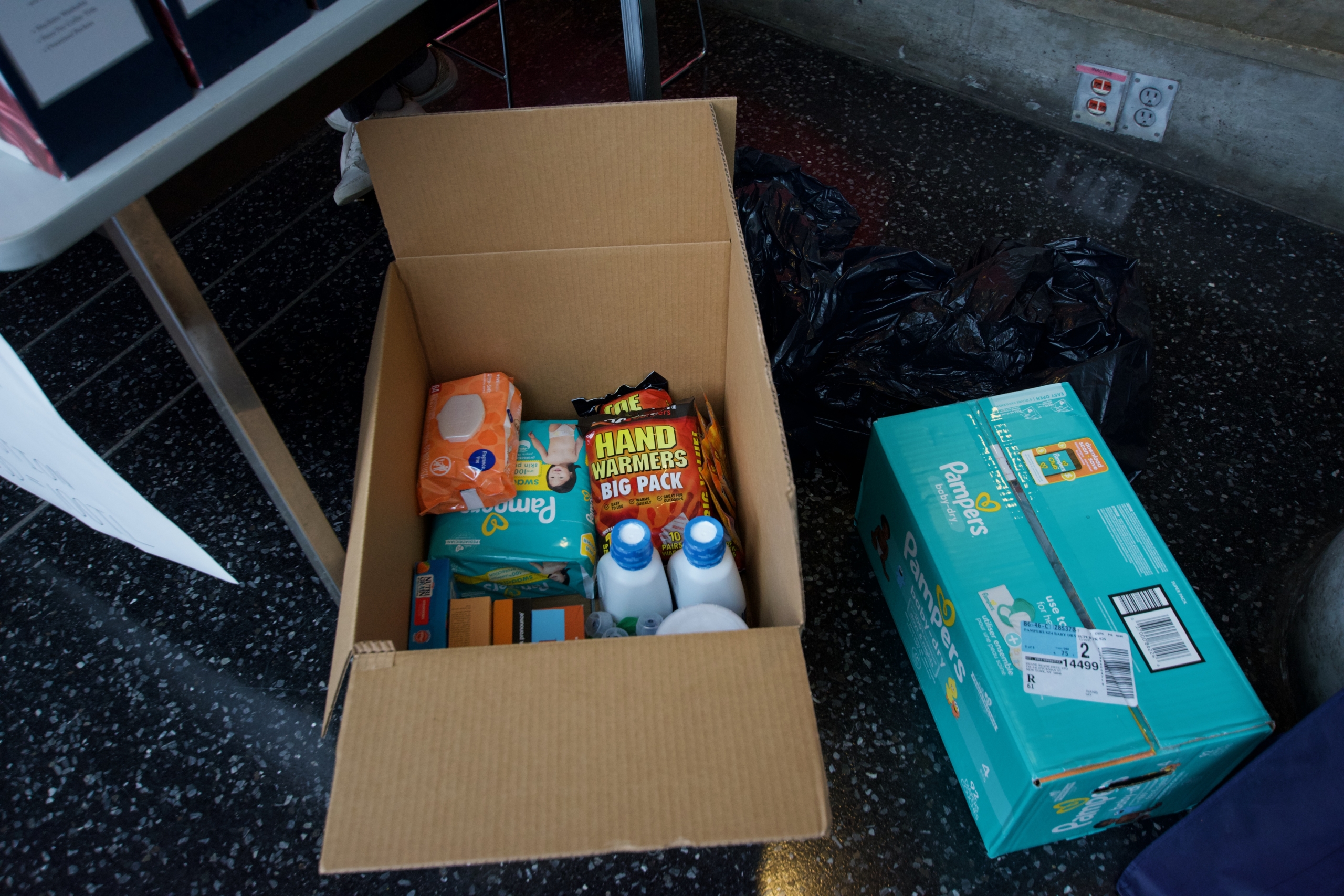

The Columbia Turkish Students Association has worked over the past week to raise awareness about the earthquake and collect money to donate to the victims. The group has about 160 undergraduate, graduate and alumni members, and it set up a stand in Columbia’s Lerner Hall to collect money, winter clothes, canned goods, and hygienic products, among other essential items to send to Turkey. “We’ve been trying to emphasize the urgency of the situation and grab people’s attention,” said Yasemin Yuksel, an undergraduate student and member of the association.

On Monday, the association had raised more than $17,000 in donations, according to the group’s Instagram account. “We thank everyone who has shown support,” said Dafne Sarfati, an undergraduate student and association member.

The goods collected in the cardboard boxes next to their stand are taken to the Turkish consulate in Midtown and then shipped on a daily Turkish Airlines flight. Besides their collecting work at Columbia, members of the Turkish student group help other volunteers at the consulate, packing and sorting donated items for shipment to Turkey.

At the consulate on Sunday afternoon, dozens of people were hurriedly wrapping boxes and loading them into trucks, stopping occasionally for tea and pastries and to share a moment of grief for those who lost everything in their homeland.

Some volunteers, like Melissa A., who declined to give her last name, were critical of the local response, saying it felt like there was less empathy and less aid than for “blonde, blue-eyed or Christian” Ukrainians displaced by Russia’s invasion of their country last year. The academic community in particular could have responded more quickly by staging fundraising events and sharing information in newsletters about how to donate, some said. Gozde D., a researcher at CUNY who declined to give her last name, said: “On Friday, we had an email saying ‘we’re with you.’ And that’s it.”

For the Syrian community in the city, the emotional impact of the earthquake has hit even harder, in part because there has been far less media coverage of the disaster’s destruction in the war-torn country. Lena Arkawi, a Syrian-American activist and founder of Sourceable, a Columbia-supported online platform to connect citizen journalists, said Sourceable’s Syrian network has greatly suffered the effects of the tragedy. “Most of them have been severely affected. A lot of them have lost their homes [and] lost family members,” she said in a phone interview.

Sami Salloum, a recent master’s graduate who studied negotiation and conflict resolution at Columbia, comes from Tartous, Syria. Salloum said he was on the subway when his mother texted the family WhatsApp group about a violent earthquake that left the cabinet doors open and smashed vases to the floor. Although his own family was safe, Salloum said a member of his extended family and his wife perished. Their bodies were found, hugging each other at the gates of their crumbling building, where they had tried to escape. “We’re just out of words,” Salloum said in a phone interview.

Salloum, who was involved in the organization of the Columbia vigil, said that the earthquake has worsened the dire living conditions of thousands of Syrians already struggling after 13 years of conflict. “The whole purpose is to raise funds and support the recovery,” he said. “It should go beyond food, water, medications, and tents. Aid should go to rebuild the houses that were destroyed.”

Almost seven million Syrians are internally displaced, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and recovery efforts will take a long time in a region already suffering a military and humanitarian crisis. “People don’t have shelters. They lost their businesses and the economic situation is already extremely dire,” said Salloum. “It’s already tragically bad.”

At 5 p.m., after a long day helping at the Consulate, some of the volunteers walked to Times Square for a vigil in remembrance of the victims. Holding Turkish flags and red carnations, people sang the national anthem and offered comforting words, crying for a tragedy that, overnight, wiped out entire cities and trapped thousands of people under the rubble of their homes. “People are not immune to pain, they get hurt the same,” said Melissa, who was moved by the solidarity and support people showed at the vigil. “Just because they don’t have money or don’t have political importance, they’re still humans, and no human life is less important than another.” Gozde said she was still processing her feelings, unable to understand the tragedy. “I kept thinking of those who suffered from the earthquake,” she said “It’s not easy.”

This article from the Columbia Daily Spectator gives more information, including some links for donating money:

https://www.columbiaspectator.com/opinion/2023/02/09/35-lives-for-the-price-of-a-coffee-help-us-support-turkish-and-syrian-earthquake-victims-despite-the-bureaucratic-hurdles-imposed-by-the-university/