By Scott Etkin

When Big Nick’s Burger & Pizza Joint on W. 77th Street and Broadway closed in 2013, it meant far more than just one less place to get a slice on the Upper West Side, says writer and longtime neighborhood resident Thomas Dyja. For Dyja, the death of Big Nick’s was a culinary symbol of the huge changes he’s witnessed in his three decades in the city — a period in which New York became cleaner and safer, he says, but also less exciting and more unequal.

“The city had changed for the better in so many ways, but it also had gotten homogenized and more boring,” Dyja said on a Zoom call from his home office on W. 79th Street, in the apartment where he has lived with his family for the past 25 years. Big Nick’s was a neighborhood institution: “You wanted it to be there. But I didn’t go that often,” Dyja said, explaining (with a laugh), “because it wasn’t that good.”

Two years ago, with the pandemic in full swing, Dyja published New York, New York, New York: Four Decades of Success, Excess, and Transformation (Simon & Schuster), his ambitious chronicle of the city’s cultural, political, and economic shifts from the start of the administration of Mayor Ed Koch in 1978 through the end of Michael Bloomberg’s final mayoral term in 2013.

Bloomberg left office the same year Big Nick’s closed – also the year Dyja began work on New York, New York, New York. Eight years later, it was published to critical acclaim (“a work of astonishing breadth and depth that encompasses seminal changes in New York’s government and economy, along with deep dives into hip-hop, the AIDS crisis, the visual arts, housing, architecture and finance,” wrote a Times reviewer.)

The book was released not long after the city became known as the epicenter of the pandemic. Many New Yorkers were fleeing to Florida or the Hamptons, or asking existential questions about the future of New York.

Dyja put it in perspective. “When you do a lot of reading about New York, and you’ve been around long enough, you find there’s always another crisis,” he told the Rag. “You have the fiscal crisis, and then you have the crisis with [Mayor] Dinkins where things look like they’re going to implode, and then you have 9/11. And every time, everybody’s like, ‘New York’s not going to come back. It’s dead.’ And somehow it comes back.”

Still, the pandemic took its toll, and the city has the retail vacancies, homelessness, and crime to show for it. On the Upper West Side, Dyja has seen a rise in sensitivity to these issues that sometimes goes against the neighborhood’s reputation for inclusivity.

“The whole reason you were [on the UWS] in 1980, and I’d like to think after that, was that this was supposed to be a more diverse place and a little more sympathetic and community driven,” Dyja said. “There was not a sense that somebody didn’t belong in this neighborhood.”

Judging by local politics (and some comments on Rag articles), we’re in a period of hypersensitivity about crime. But again, Dyja suggests this period may not be unique. “You put a few million people together [and] stuff happens,” he said. In reading past newspapers for his book,“every time I hit an election cycle, there’d be this huge run up about crime,” Dyja said. “And then suddenly no one would be talking about it after election day.”

The UWS has come a long way from the danger of the 80s, when “you would never go into Riverside Park in anything other than broad daylight,” Dyja said. He sees the need for more housing, especially for underserved people who were “elbowed out of the neighborhood” when single-room-occupancy apartments were converted into multi-room units. “Between 1970 and 1983…87 percent of the city’s S.R.O. rooms disappeared,” according to The New York Times. “In 1993 there were 44,000 rooms [of 200,000] left in New York. Many people who would have been S.R.O. tenants ended up homeless.”

The forces that knock New York down and build it back up are messy. To make sense of it in his book, Dyja highlighted some of the key people – such as Parks Department Commissioner Gordon Davis and AIDS activist Larry Kramer – who dug in and took responsibility for problems that seemed intractable at the time, who found solutions — or at least paths to great improvement.

Although Dyja lived here through the years he covered in the book, he went back to contemporary written materials to fact check his memory. His research led him to read “literally every issue of New York magazine, to know not just what happened, but how people were looking at it,” he said. “If more of the [Village] Voice were available online, I’d probably still be reading it.”

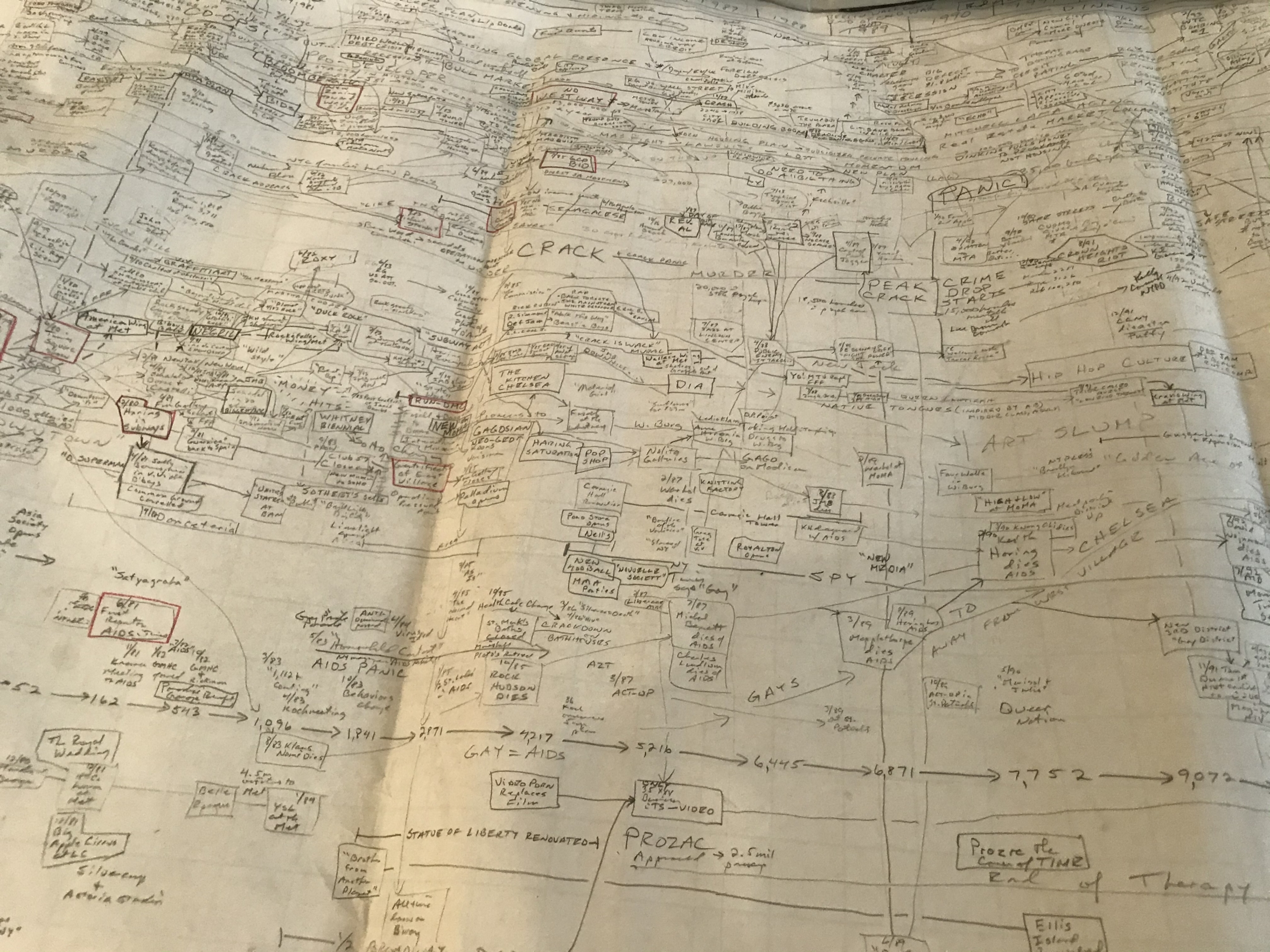

To make sense of the research, Dyja taped together a handwritten, eight-foot timeline, which helped him keep track of the plot, themes, and characters over the decades.

Dyja sees parallels between his 12-story apartment building and the city’s bruised history and enduring potential. The building isn’t perfect – it has been broken into (it “ain’t the Apthorp,” he said), but it works for everyone who calls it home.

“Over time, you had different kinds of people coming in, different types of money, different types of jobs. [The building] brings that all together into a place that functions and that’s respectful and keeps everybody’s needs and desires in mind as it goes forward,” he said. “It became, for me, a miniature possibility of how we can do things here in the city and how we need to work with each other to keep it going.”

Wow, that timeline is amazing!

If you would like to see what the West Side looked like from the 1970s until the early 2000s, watch You’ve Got Mail. Change came slowly. Now, you blink your eyes and a block is different. I so miss the fried pork chops at Caridad at 78th and Broadway.

well, if you try the fried pork chops at Dinastia on 72nd, you might wonder why you loved those at Caridad as much as you did. it’s been there a very long time.

I’ll have to check it out. Some days I wake up thinking about those green plastic plates in Big Nicks and the luncheon special. I also spent too much time in Teachers and spent too much money in Charivari.

Oh my, which Charivari did you go to then? There were too many on Upper West Side in 1080’s. Workshop was my store.

Maybe. But La Caridad had the world’s best and most authentic wonton soup as well. And the best ropa vieja and egg rolls, too!

Big Nick’s was at 71/Columbus

Big Nick’s Too was not owned by Nick Imirziades, who owned the Big Nick’s Pizza Joint and Big Nick’s Burger Joint on Broadway.

The Columbus Ave location was a different/newer Big Nick’s.

The original Big Nicks (Broadway/77th) was open 51 years from 1962 to 2013.

https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/big-nicks-restaurant-closes-after-51-years-on-upper-west-side/

There were 2. The biggest at 77th & a smaller one on 71st & Columbus which stayed around a bit longer but is also closed.

There was also one on 77 and broadway…we were lucky to have dual oitposts

I’ve lived on the UWS for 45 years. I would never leave. It has had ups and downs, but that’s what makes it great. There is always something to love, or hate. UWSers, love to have an opinion about everything. I have to read this book now.

Oh, and there were 2 locations for Big Nick’s. But Broadway was the original location.

Three, actually: Nick also had the widely forgotten Burger Joint Too, AKA Burger Joint II, at 438 Second Avenue in the mid-1980s.

Perhaps a dozen people in the universe remember this.

would love to have a print-out of the TimeLine to hang on my wall. Any hope of that?

Couldn’t resist sharing this story about the original Big Nicks on Broadway. I ordered a hamburger. The first bite surfaced in my mouth a lump. I spit it into my plate. It was a spiral steel scrub brush fragment, sharp at the edges, and “not healthy”. I called Big Nick’s attention. His response was: “Wanna nother burger?” Nuff said.

Having lived on the UWS – in the same apartment – since 1965, I could write an even longer book, which would include more than an additional two decades prior to Mr. Dyja’s residency. I could talk about going to school as a child and teenager (PS 9, IS 44), doing community work (Community Board, Precinct Council, etc.), and working with the street homeless for almost 20 years (as a minister).

I could mention the “overdevelopment” in the 1980s and 90s, when condos and coops were going up so quickly that developers could not even fill them with the “upper middle class” (read “wealthy”) who could afford them, and whose development and construction led to the loss of truly affordable housing (including, as Mr. Dyja points out, SROs and other housing for the neediest among us). It is not a coincidence that the UWS’ – and NYC’s – first, and arguably most drastic – increase in homeless occurred during these two decades.

I could also mention “empty storefront syndrome” (initially a function of landlord greed and financial chicanery vis-a-vis taxes and lack of commercial rent control, it has been exacerbated by the invention of the Internet and online shopping, and by the pandemic), causing the loss of “mom and pop” shops and independent stores (some owned by local residents) in favor of “big box” stores and “chains” – which are now, themselves, being lost. When large chain stores (and even banks) cannot afford the rents, there is clearly a HUGE problem.

And I could mention the changing demographics of the neighborhood, including an influx of more “conservative” types who do not have the same acceptance of diversity that the UWS has historically had. The most recent, and vicious, example was the reaction of some to the homeless being placed in local hotels during the early stages of the pandemic.

During the first 10-15 years of my residency here, the UWS became the true “s—hole” that some still remember, with junkies and needles everywhere, prostitutes on many corners, robberies of merchants, apartments, and people at an all-time high, gang violence, and even semi-regular shootings, mostly on Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues.

Things began to calm down in the mid- to late 1980s and early 1990s, and from then until the 2010s, things got a lot better – though, as Mr. Dyja suggests, they also got blander and more homogenized through gentrification.

Still, I would not trade being an UWSer for being a resident of any other neighborhood in NYC. It’s been a roller coaster ride in some ways, but it is absolutely “home.”

Mr. Alterman: if you call someone “conservative” because they don’t want addicts shooting up on our corner and overdosing in CVS – you’ve got a really skewed definition of the word. No matter…the UWS is like a 3rd world country. It has deteriorated into a dark depressing dirty neighborhood ..no stores, no conveniences, nothing pleasurable or likable anymore. You ought to take a bus across town on 72nd or 79th….that is what NY means …this “s—hole” that Broadway in the 70’s has become is not anyone’s idea of liveable.

As a fellow UWS lifer – hear hear

Been in the neighborhood about as long, and I agree that it is home. With its dysfunction, and constant evolution and devolution and shifts and turns and dings and betterment. There’s much to critic, and much to cherish. Not in an idolizing way, but in the real way living neighborhoods are. For the UWS is first and foremost the people. The everyday interactions, some big, some small, all potentially meaningful. Imperfect and woefully ready for improvement (aren’t we all?), I would not want to live anyplace else in NYC. (And, of course I’m gonna read this book now!)

Hear, hear!

The one comment I have is that I moved to the UWS, 89th St between West End and Riversisde in the70s when Abe Beame was mayor. Because of what the city was in the 1970s , by the time we reached the 80s, the city and this neighborhood were looking very safe and very much improved. Its really a matter of your point of reference.

I moved onto Claremont Ave in fall, 1975. I remember standing in the linoleum-floored kitchen listening to WINS give the blow by blow of the City’s declaration of bankruptcy.

Great interview, and good on Dyja for giving it to the “new people” for their shrill histrionics

Pretty sure “shrill histrionics” is what the frog was saying while the water in the pot around it was warming up.

Disagree with Dyja — Big Nick’s had the best burgers — and was famous for that!

He also opened that fabulous little restaurant (also Nick’s) that had the best steak sautee bordelaise.

The original Big Nick’s, when it was on Broadway, had burgers and chicken sandwiches that were simply amazing and people went out of their way for them.

Remember when Barnes and Noble was the evil empire driving Skakespeare and others out of the UWS?

Let’s not forget to buy Dyja’s book there not Amazon.