By Peggy Taylor

“Take the kinks out of your mind instead of out of your hair.”

~ Black Nationalist and Separatist Marcus Garvey

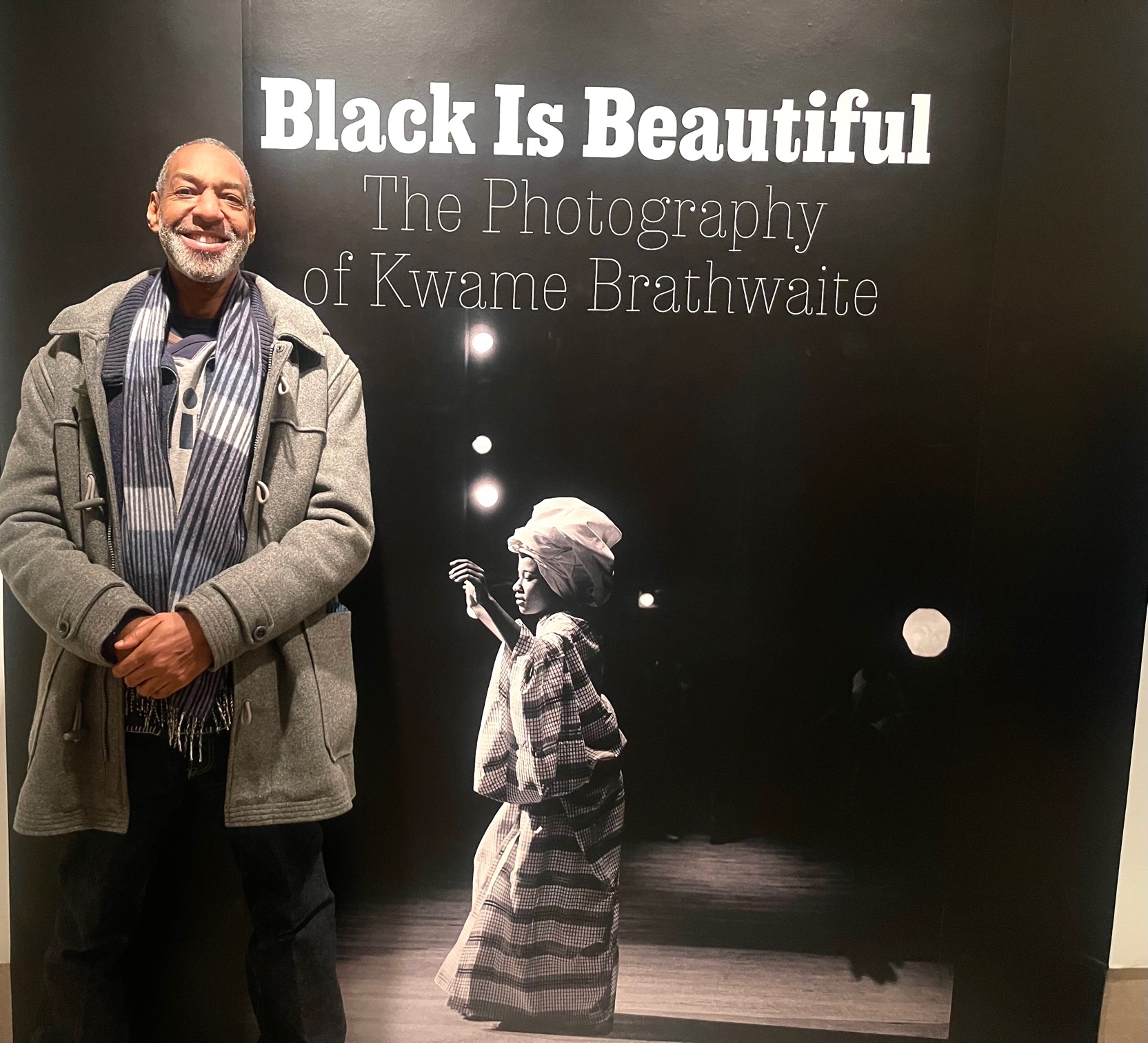

“My hair is not up for debate,“ reads a souvenir pin in the New-York Historical Society’s gift shop, alluding to the work of Harlem artist-activist Kwame Brathwaite, whose photographs are on display at the museum through this Sunday, January 15.

But on viewing the exhibit, one has to conclude that black hair, on both women and men (remember conks?), was very much up for debate in the 1960’s, when Brathwaite, born into a family of artists, entrepreneurs, and Black nationalists, embraced Garvey’s motto: “Take the kinks out of your mind instead of out of your hair.”

One of the most illuminating photographs of the exhibit is that of three Afro-sporting Black women (including Kwame’s sister-in-law, Nomsa) picketing the white-owned “Wigs Parisian” shop in Harlem while brandishing posters reading: “Natural, yes! Wigs no!’ Not pictured in the exhibit, however, but shown in the accompanying souvenir book, is a photo of a counterprotest of Black women with straight hair carrying posters reading: “Beauty is personal; decide for yourself.“ “If it looks good, wear it!”

When I viewed the exhibit, one of the visitors, Harlemite Monte Jackson, custodian at the Board of Education, had a group of us in stitches as he described the ordeal of two Virginia cousins having their hair straightened by his great-grandmother. “She had this iron comb which she heated on a burner on the stove; she kept telling them to sit still, but they didn’t, and so she accidentally burned their ears and necks and then rubbed the burned spots with Dixie Peach grease. When another cousin came into the room and asked what he was smelling, I said, ‘It’s your cousins’ heads cooking.’”

Amusing stories aside, the exhibit is not just about black hair, kinky or straight. It’s about black fashion (men and women sporting African garb), black entrepreneurship (opening up businesses like Brathwaite’s father’s two dry cleaners and tailor shops), black economic empowerment (“Buy Black”) and black solidarity with African liberation movements (Kwame and Elombe arranged for Nelson Mandela to visit New York after his 27-year imprisonment.) In the words of historian Tanisha Ford, the exhibit’s text writer: “The brothers were calling themselves African and Black long before those terms became common in American racial vernacular. They were the woke set of their generation.”

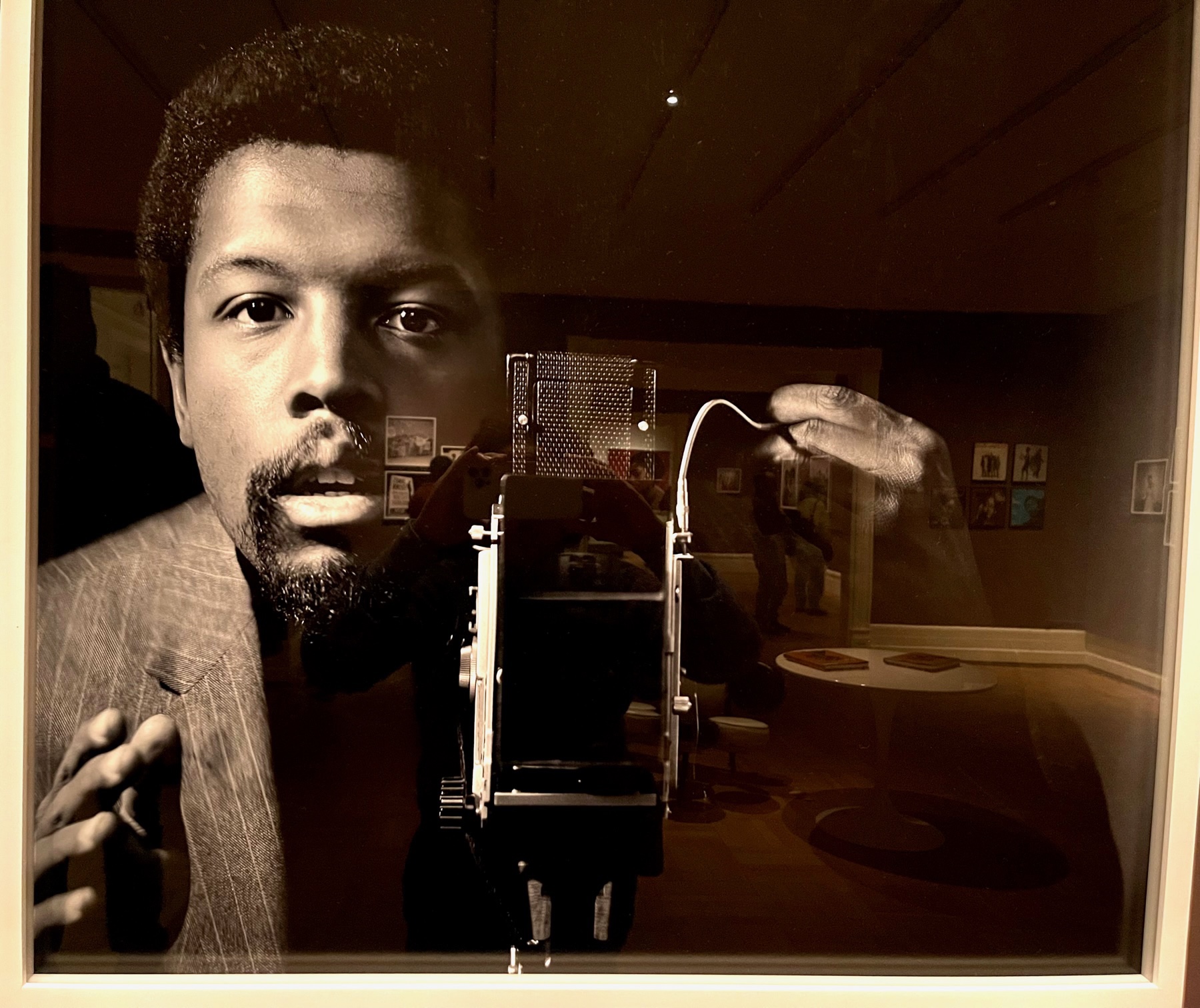

The sons of Barbadian immigrants, Kwame, born Ronald, and brother, Elombe, born Cecile, attended the School of Industrial Art—-now the High School of Music and Design. After graduating, they co-founded AJASS, the African Jazz-Art Society and Studio, a radical collective of playwrights, photographers, sculptors, graphic artists, dancers, and fashion designers. They promoted jazz, which they considered the music of rebellion, and brought it back uptown after it had migrated downtown. Kwame photographed jazz greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, and Count Basie. Elombe designed the album covers and put dark-skinned, Afro-sporting models on those covers, something unheard of in those days.

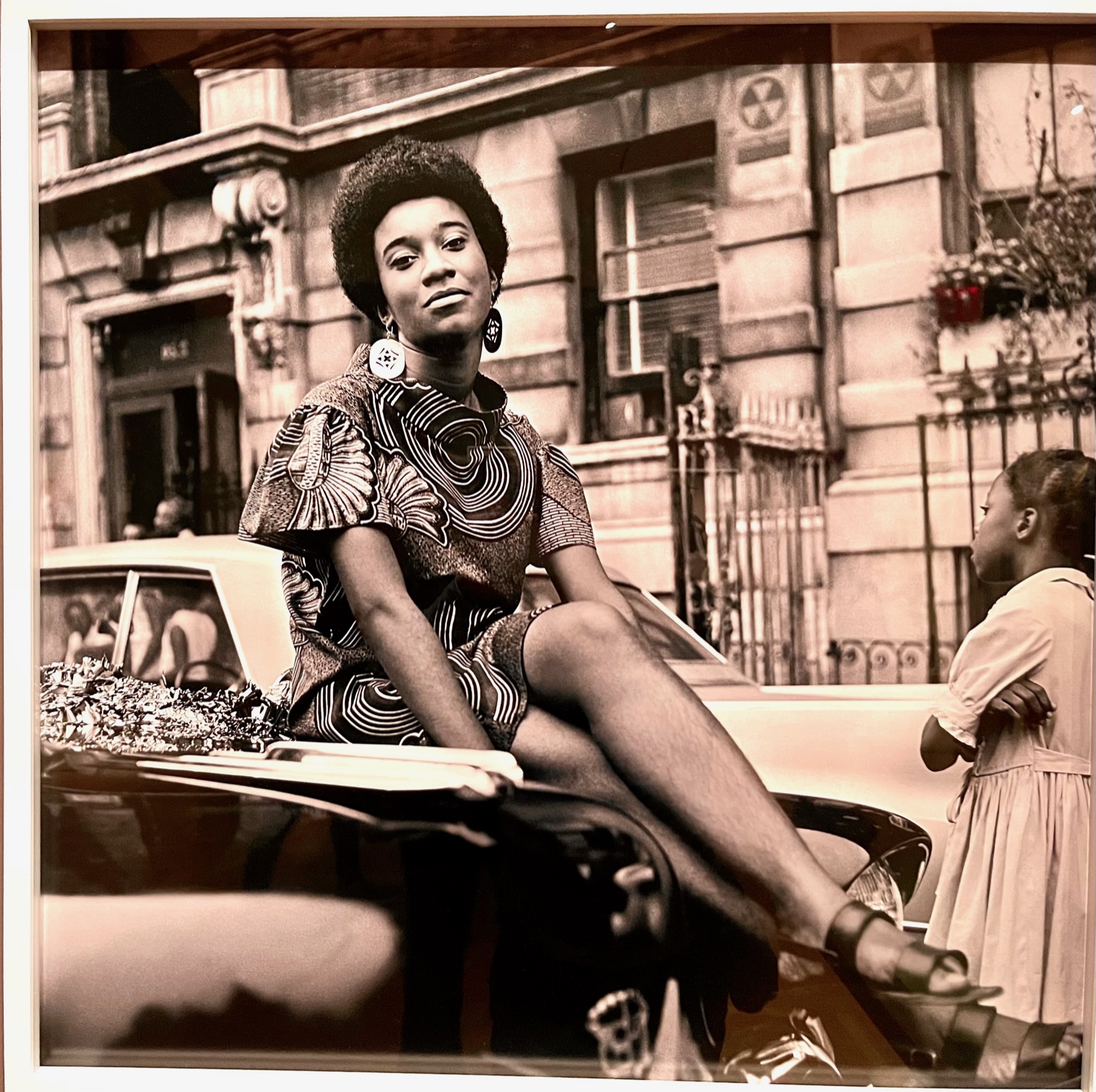

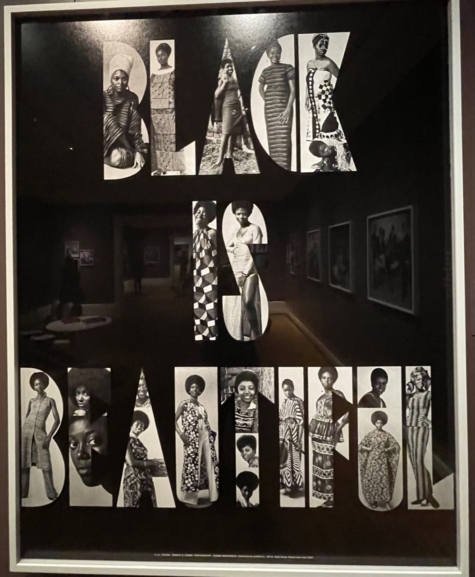

In the early 60’s, after having founded a theater troupe, they founded a modeling troupe called Grandassa, which celebrated the beauty of Black women’s bodies and natural hair through fashion shows and photography. The Grandassa models were the first to openly promote the slogan, “Black is Beautiful,” thus challenging conventional beauty standards and bucking the European-dominated fashion trends of the day.

The Grandassa Models often designed and sewed their own clothes, used Kente-cloth wrap skirts, and bold, colorfully patterned dresses. In her book, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul, Ford writes: “Clothing was part of the political message and ideology. Black women were encouraged to be their authentic selves. They were beasts with sewing machines and stitched their sartorial dreams into existence.”

Kwame and Elombe founded a “Miss Natural Standard of Beauty” contest and staged annual, sometimes biannual, pageants called “Naturally” at the Apollo Theater and the recently and controversially razed Renaissance Casino and Ballroom.

But these ‘Naturally’ extravaganzas were more than fashion shows. They were also fund-raisers, consciousness-raisers, opportunities to spread the Garvey message and hear speeches by African freedom fighters. It was all intermingled—-fashion, entrepreneurship, Black liberation, Black empowerment—and this gave a fuller meaning to the “Black is Beautiful” slogan.

To be especially noted is that all this struggling, striving, innovating, and creating was taking place against a backdrop of tragedy and loss—-the Vietnam War, the crack epidemic, and Harlem gang warfare. But despite all this, the Brathwaite brothers kept pursuing their goals of fostering Black empowerment and pride.

The photographs in this exhibit are not just random shots taken on the streets of Harlem. The Brathwaite brothers created the scenes and events which Kwame photographed, and which this exhibit celebrates.

The photographs in this exhibit are not just random shots taken on the streets of Harlem. The Brathwaite brothers created the scenes and events which Kwame photographed, and which this exhibit celebrates.

HS of Industrial Arts became HS of Art and Design

Superb review.

that is a great show and highly recommended to anyone interested in photography, NYC history, or African American culture. Prints are stunning too.

Thanks for the tip and this review, Peggy. Will definitely check out this show before it closes.

Peggy, your message about your article showed up just before I heard an interview on Alison Stewart’s “All of It.”about the exhibit. The synchronicity compelled me to see the show before it closed. I reveled in the elegance and power of the women. The subtle photograph of the man listening to jazz as the smoke from his pipe curled in the air pulled me into the scene. Thank you for this fine review.