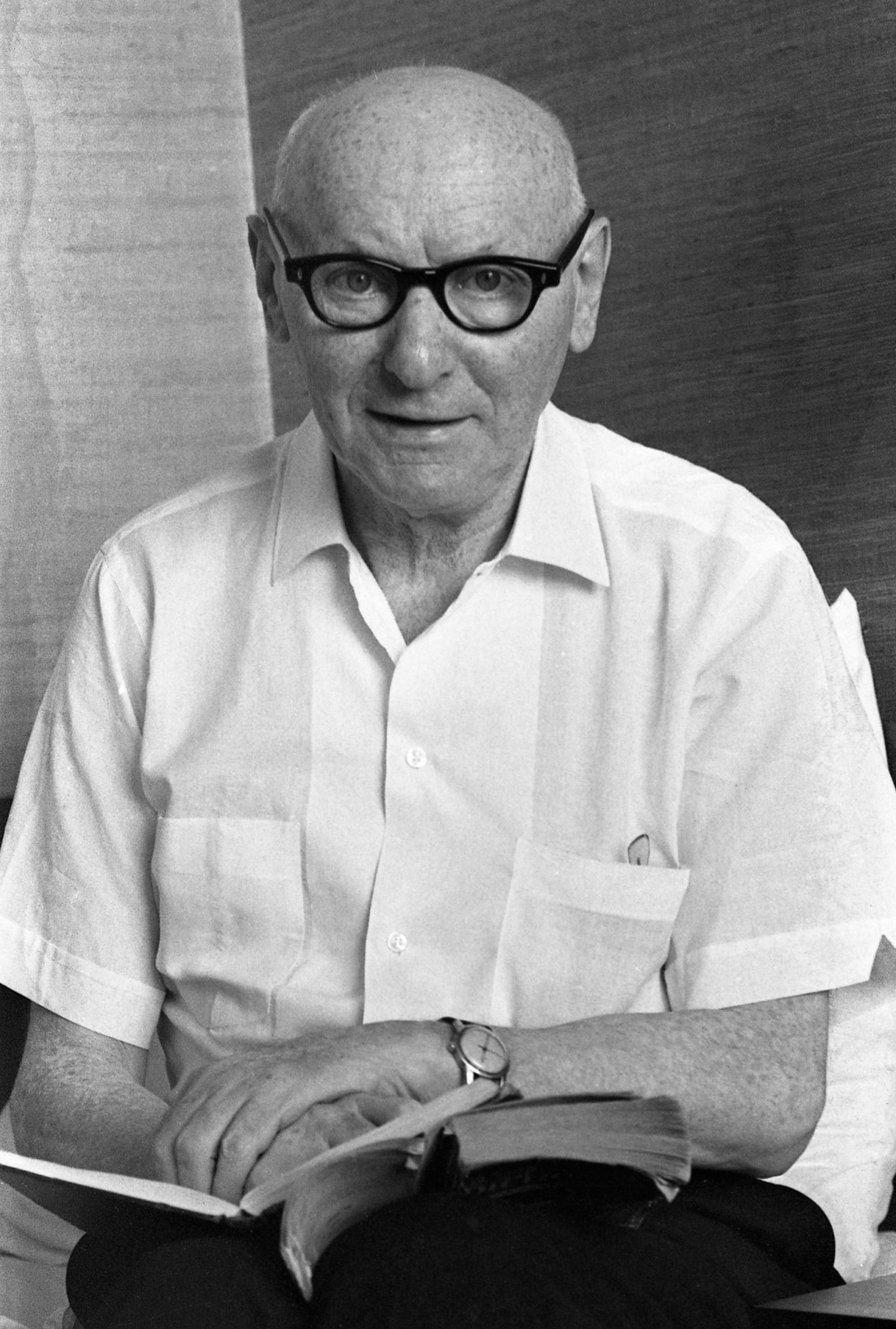

In July, the Rag asked (and answered) What Do You Have to Do to Have a Street Named After You? We also invited readers to ask us about the stories behind the names on Upper West Side streets. Today we’ve got the story of Nobel Prize-winning author Isaac Bashevis Singer, who immigrated to New York in 1935 and moved to the UWS a few years later. The neighborhood was the backdrop in some of his stories, and The New York Times once called him “the grand old man of the Upper West Side.” Send us a note at info@westsiderag.com to suggest what street sign we should investigate next time.

By Daniel Krieger

For Isaac Bashevis Singer, the Nobel Prize-winning literary giant, the Upper West Side played a major role in the story of his own evolution. It was where he found his footing as an artist and grew into a new and fruitful life in the United States.

Born in Leoncin, Poland, in 1904, he spent his childhood in Warsaw and various Polish shtetls. In 1935 he emigrated to New York, after presciently deciding that the metastasizing Nazi threat in Germany was going to be very bad for the Jews. He landed in Brooklyn, and things were tough going at first. He felt lost in this foreign country, where literature written in Yiddish seemed dead. But then, around 1941, he and his new wife, Alma, whom he met a few years earlier in the Catskills, moved to 410 Central Park West near 100th Street. Soon after, Singer began to hit his stride — prolifically writing fiction as well as contributing journalism to the Yiddish-language newspaper, The Jewish Daily Forward (The Forward still publishes, in Yiddish and English).

Singer stayed put on Central Park West for about 20 years until he was robbed at gunpoint in his apartment lobby. He moved briefly to West 72nd Street, then, in 1965, to The Belnord, a humongous Renaissance-style limestone rental building that takes up an entire square block on West 86th Street. When it was finished in 1909, it was the talk of the town, and according to this recent New York Times article about it, has been ever since.

Toward the final years of his life, Singer began spending most of his time in Surfside, Florida, though he never gave up his rent-controlled apartment at The Belnord. One year before his death in 1991, West 86th Street from Broadway to Amsterdam was named Isaac Bashevis Singer Boulevard in his honor. (The street where he lived in Surfside was also named after him.)

Dressed in a suit and tie, Singer was a common sight taking long walks around the neighborhood for decades — up to six miles a day, according to his personal assistant — and The New York Times once called him “the grand old man of the Upper West Side.” He was deeply connected to the local community, and had a reputation for being a talker, both in Yiddish and his heavily accented English. He liked going to restaurants, all now long gone, known for their Jewish fare, where he would mingle and gossip with other Yiddish-speaking refugees who flocked to New York in those days. There was The Famous Dairy Restaurant on West 72nd Street, where The New York Times reported in 1991: “He almost always had the $5.50 lunch special of vegetarian chopped liver — a concoction of carrots, peas, string beans and onions —and the soup of the day.”

Singer also frequented the American Restaurant, his local coffee shop, on Broadway and 85th, which had “a false-brick facade and gilt chandeliers” and where he ate “several times a day, savoring the pea soup, boiled potato and rice pudding.” There was also Café Éclair, a Viennese pastry shop and restaurant on Broadway where, the Times reported, Singer often had “an open-face tuna-salad sandwich and a cup of coffee and occasionally a delicacy like borscht with a boiled potato and an extra dollop of sour cream.” Another of the modest places he frequented was the kosher luncheonette Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant on Broadway between 81st and 82nd Street (now occupied by The Town Shop). Being vegetarian, like his literary ancestor, Franz Kafka, Singer was especially fond of veggie burgers.

Singer made the Upper West Side the setting for some of his stories, such as “The Cafeteria,” published in The New Yorker in 1968. The narrator in the short story describes a life that is nearly identical to Singer’s: “I have been moving around this neighborhood for over thirty years — as long as I lived in Poland. I know each block, each house … and I have the illusion of having put down roots here. I have spoken in most of the synagogues. They know me in some of the stores and in the vegetarian restaurants … even the pigeons know me; the moment I come out with a bag of feed, they begin to fly toward me from blocks away.”

His most famous novel that took place on the Upper West Side is “Shadows on the Hudson,” which a New York Times reviewer called his “masterpiece.” The novel is infused with a harshness and the kinds of things that turned some Jews against him, like comparing God to a Nazi; themes of amorality and betrayal; self-loathing Jewish characters who say things like, “God Himself is the worst murderer.” It features an array of troubled, affluent Jews living on the Upper West Side after World War II, many of whom are portrayed unsympathetically – like the stockbroker obsessed with sex and money and the rich Orthodox man devoid of compassion.

For this reason, as with fellow Jewish Upper West Side writer, Philip Roth, Singer had his share of detractors who criticized him for portraying Jews darkly in his fiction. Over the years, he has been referred to as a “traitor to the Yiddish tradition,” “a pornographer,” “an Anglicizing panderer,” “a dirty old man” and his writing was said to be “bad for the Jews.”

But he also got heaps of praise and was widely seen as a literary genius. He won the National Book Award in 1970, and in 1978, he became the only Yiddish-language writer to win the Nobel Prize for literature. The Swedish Academy described his ”impassioned narratives which, with roots in a Polish-Jewish cultural tradition, bring universal human conditions to life.’’

A savvy promoter of his work, Singer understood early on that to be a successful American writer he had to get his writing translated into English. He worked closely with translators on the English versions of his work and came to call English his “second original language.” He would always publish first in Yiddish, and then later he would put out a more polished, sometimes even different, English-language version. This began in 1953 when critic Irving Howe came across Singer’s short story, “Gimpel the Fool.” Recognizing a major new writer, Howe convinced Saul Bellow, who himself spent some time living on the Upper West Side (where he set his novel “Seize the Day”), to translate it. Then Howe sent the translation to an editor at the Partisan Review. Singer was off and running from that point, as the translations of his work flowed. He was published regularly in magazines such as the New Yorker, Playboy, and Harper’s.

In the first Singer biography, “The Magician of West 86th Street,” Paul Kresh poses the question, “What is Isaac Bashevis Singer?” His answer, in part: “He is a man of many paradoxes and contradictions, yet withal a man, like Whitman’s poetical self, large enough to ‘contain multitudes,’ reconciled to the war of forces within himself and somehow at ease with himself.”

A mid-1980s PBS profile of him can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/YPDowgxqqjA

The novel that he wrote that, to my mind, most closely ties to the UWS was posthumously published in 1998 — “Shadows on the Hudson”. Reading it at the time, the characters felt very much like people I knew growing up, although I never met Singer himself to the best of my memory.

It should be said that as time has passed, some of his more unsavory behaviors have come to light, like with Phillip Roth.

Born and raised on the UWS, when I was at UMASS, 1987 Freshman Year English the professor, was talking about Isaac Bashevis Singer and I mentioned that he grew up on the UWS and had a street named after him. He told me I was wrong. I insisted but he told me that was not true. I was 18 and a Freshman at UMASS, but I stood up to him and told him that he was wrong and that Isaac did and that the sign was on 86th street. He again doubted me and told me I was wrong in front of the whole class. (Wish I had a cell phone then) 🙂

Rest assured, Singer did not grow up on theUWS.

I met him once. At the Yale Repertory Theatre where I worked and he visited for the premiere of his short story Gimpel the Fool.

Thank you for sharing! I am wondering if American Restaurant, his local coffee shop, on Broadway and 85th, is now the site of French Roast. Anyone know?

Yes!

Yes.

YES IT IS THE SAME locatiom as French Cafe.! I was living at Breton Hall on Broadway and 86th and walked one wintry morning to the coffee shop for breakfast. I saw an older couple coming down the block toward me – in winter coats, hats and scarves., so I held the door for them. The woman asked,”you know him?” I said, “no” and she said, “just a nice lady”. I went to the counter to order my breakfast and noticed the couple taking off their winter coats and sit at a booth. I had just heard Mr. Singer speak and read at a church in Montclair and bought Mazel and Schlomazel (?) for my sons. I asked the waiter “Is that Mr. Singer?” Yes,” he replied, “He comes for breakfast every morning.””Gathering my courage I went over to the table and they invited me to sit down. I had been doing a project for the 92 St Y, and had to frame and have photos signed by all the luminaries who had spoken or performed there. When I told him I need his signature on one of the photos, he said, of course”, bring it over. I live on the corner. “I went with the photo and spoke to the doorman who told me to go right up.I didn’t want to disturb him so left the photo with the doorman. What a missed opportunity.!The doormen loved him so much, they all had his photo in their wallets.

Yes, that was where the American Restaurant was. And I sat next to Singer one afternoon and he complimented me on my beautiful baby boy, who was actually my beautiful baby girl

Yes I met him at the American Restaurant, which I used to frequent; we had a lovely conversation that for the most part consisted of me happily thanking him for all the lovely hours I’d spent with his fascinating creations, which conversation (the specific details sadly missing) is still one of the highlights of my long life.

I’d bitterly resent that chi-chi Roast for having usurp my hangout, the home of many wonderful cheeseburgers and the second home of a Nobel prize-winner, except if I bitterly resented all the joys and comforts of the past that are now entirely gone (like, for example I.B. Singer himself) I’d have to immediately throw myself from the nearest window (defenestration)…

and then where would I be?

I’d like to extend my remark from above, if I may. IB Singer was a literary giant who lived a long life & is well remembered. His older brother IJ (Israel Joshua) Singer was a literary giant as well. He was also a painter. Unfortunately, though he was extremely talented and accomplished, he did not enjoy a long life.

According to Wikipedia: “Singer contributed to the European Yiddish press from 1916. In 1919, he and his wife Genia went to Ukraine, where he found work on a newspaper, The New Times, and was considered one of the “Kiev Writers”. Then they moved to Moscow, where he published articles and stories. After two hard years, in 1921, they returned to Warsaw. In 1921, after Abraham Cahan” (one of the founders of The Forward) “noticed his story Pearls, Singer became a correspondent for the American Yiddish newspaper The Forward. His short story Liuk appeared in 1924, illuminating the ideological confusion of the Bolshevik Revolution. He wrote his first novel, Steel and Iron, in 1927. In 1934 he emigrated to the United States to write for The Forward. Eventually, Israel Joshua invited his younger brother, the future Nobel prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer, to the United States and engineered for him a job with The Forward…”

My personal favorite among IJ’s many novels, my highest recommendation, is “The Brothers Ashkenazi”. When published, it was on top of The New York Times Best Sellers list, along with Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind.

“He died of a heart attack at age 50 in New York City, 258 Riverside Drive on February 10, 1944.” (Wiki again)

If it was up to me, New York City would name a street, maybe even Riverside Drive, after IJ Singer as well, but my telephone remains silent; my counsel, wise or otherwise, has not yet been sought by the officials who make such weighty decisions.

I think it’s possible, had he lived longer, that he too might’ve won The Nobel Prize For Literature.

I give you: The Brothers Singer.

Second the motion on The Brothers Ashkenazi.

I lived at 51 W 86th St in the late ‘70s/early ‘80s and saw Singer occasionally coming and going – I believe his assistant or translator lived in our building. Star struck!

In 1994 Metropolitan Diary published this squib I submitted:

I note with delight that the city has designated that 86th Street from Broadway to Amsterdam Avenue be named in tribute to a former resident, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and I also see that his favorite cafeteria is now a clothing store. So I wrote my own celebration of sorts:

STREET SIGN

Here’s a real humdinger

That caught me off my guard:

Isaac Bashevis Singer

Is now a boulevard.

West 86th, I see,

Has put him on the map.

Where Singer used to be

You now will find a Gap.

Jeff Kindley

In the documentary Unmasked, Philip Roth (comparing some Jewish criticism of his own work to similar earlier criticism of Singer’s work) says Singer was asked, “Mr. Singer, why must you write about Jewish whores and Jewish pimps?” and that he replied, “What should I write about? Portuguese whores? Portuguese pimps?”

He did a reading a reading a Eeyore’s sometime in the early 80’s when my son was 3 or 4. His wife and I discussed favorite restaurants in NYC and Florida. She became taken with my son and wanted to buy him a gift. I had her sign the box of something we purchased. Very lovely, down to earth person.

Thank you for this. What a great article.

Although I lived a few blocks from the Belnord, it took a trip cross-country, to the Berkeley Writers’ Conference in the 1980’s, for me to say “Hello” to Mr. Singer. And that was all I got to say, because his wife, Alma, rather forcefully discouraged conversation with female participants in the workshops for aspiring writers. He was quite elderly at the time, but his talks were engaging and lively. He stayed away, however from the after-hours parties, which were quietly riotous. Too bad; I would have loved to share a glass of milk or seltzer with him. It pleases me now that the block signs memorialize him.

I am shocked that this article doesn’t mention that the successful TV series “Only Murders in the Building” is filmed at the Belnord. Mr. Singer would probably have liked that, particularly given that I remember that Steve Martin acted on one of Mr. Singer’s plays.

Also, if memory serves, Cafe Eclair was not on Broadway, but on West 72nd Street, between Broadway and Columbus.

Finally, one of Singer’s Belnord neighbors and friends was Art D’Lugoff, owner of the Village Gate. The two ate together at the American Restaurant on occasion.

I remember the American Wow. And my mom when she first moved here, used to eat at the place on 72ns. Still talked about it.