By Peggy Taylor

Ellen V. Futter, President of the American Museum of Natural History, in COVID quarantine, missed the preview of the Museum’s oldest gallery, the Northwest Coast Hall, which will open to the public on May 13. But she marked the momentous occasion via Zoom and greeted co-curators from Indigenous Nations saying, “This fully reimagined and gloriously reinvigorated Hall would not have been possible without you.”

Although the Hall has existed since 1899 when it became the first permanent exhibit dedicated to the interpretation of cultures, it has always interpreted those cultures without input from the members of them. That has now changed. After a five-year, $19 million renovation, the 1,000-plus artifacts on display are being interpreted by the Indigenous communities themselves.

For five years, they collaborated with the Museum’s Curator of North American Ethnology, Peter Whiteley, to showcase the gallery in a new, more meaningful way. Consultants from nine indigenous communities have also worked under the leadership of Nuu-chah-nulth Scholar and Cultural Historian Haa’yuups, who, unfortunately, like President Futter, could not attend the preview.

The two leaders were absent, but the co-curators were great stand-ins as they made the artifacts come alive with stories, songs, and dances to the sound of deer toes rattling from their elaborate ceremonial robes. They performed under the largest, (65-foot-long) Northwest Coast dugout canoe in existence, which, once again suspended from the ceiling, allowed attendees to fully admire the Haida and Haílzaqv designs adorning it.

The presentations were so powerful that some attendees wished the performers were a permanent part of the exhibit. But David A. Boxley noted “We’re not museum exhibits. We’re a living, proud people, and we’re going to continue.” (This quote from one of the exhibits.) Garfield George of the Deisheetaan Clan, Tlingit Nation, agreed, “People look at these artifacts and think wow, that’s nice. But they think we’re a dead culture–that we are not here anymore. But we say, we are still here on our grandfather’s land.”

The artifacts, not all new, are divided between eight alcoves and four corner galleries representing 10 nations. The alcoves have been reconfigured with walkways that ease visitor circulation and, on a conceptual level, reflect the porosity between these communities.

Unlike the original gallery, which opened directly onto the display cases of artifacts, the reconfigured gallery begins, on the right, with a video featuring Indigenous experts explaining the history and persistence of the Northwest Coast peoples. On the left, the exhibit, “Our Voices,” focuses on issues such as environmental conservation and racism.

“Nothing about us without us,” said James McGuire, Repatriations Curator at the Haida Gwaii Museum in British Columbia, “We’ve gone from being a people being studied to a people telling our own stories.”

THE QUESTION OF REPATRIATION

One of the big concerns of Native Americans, and one confronting museums throughout the world, is that of repatriation. In the ongoing process of discovery, representatives of Indigenous cultures have reviewed items retrieved from the Museum’s storerooms and found extraordinary treasures that were never on public display. Since 1998, the Museum has returned 1,850 objects of importance to American Indigenous people, guided by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

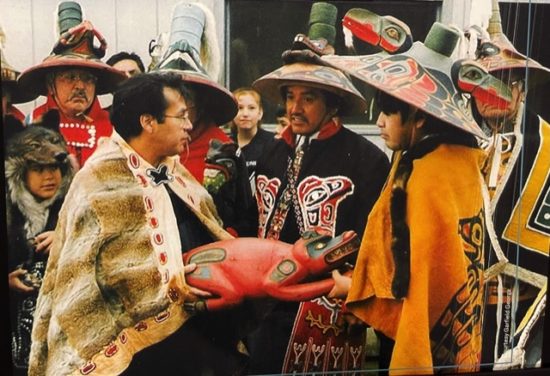

An example of an artifact that the Museum returned to the Tlingit people is the beaver-shaped canoe prow of the only canoe to survive the bombing of a Tlingit village by the U.S. Army in 1882 in Angoon, Alaska. In 1999, a Tlingit delegation discovered the beaver in the Museum and called for its repatriation. Today, it takes part in every Tlingit ceremony as a reminder of hardship, resilience and healing.

For more information, click here. The American Museum of Natural History is located on Central Park West between 81st and 77th Streets, and is open Wednesday to Sunday, 10am to 5:30pm.

Excellent!

Well, this sounds successful. I just can’t help but wonder about what seems to me to be the heart of the endeavor, “ it has always interpreted those cultures without input from the members of them”. People, institutions, museums, universities, do this ALL the time. Will they then learn to apply this concept to other people and places? What about revisionist history?

I’ve seen art exhibits where the curators make definitive statements about an artist’s work that was more like an assumption. And they give no context. These are museums to which I don’t return. Amazing how small the list becomes.

When I hear some truth about Reconstruction, maybe I’ll believe an experiential mindset might apply to everyone equally. I don’t know if we’ll ever get there. But at least now, this group gets some change in their representation/documentation.

It was so much better when the dugout canoe was displayed on the floor, as it was inside the 77th Street entrance years ago, rather than suspended from the ceiling.

Fascinating, I can’t wait to go! What a wonderful new old exhibit!

Beautiful article as anything that Peggy Taylor does turns out to be!

Thank you, Maurine!

For those who wonder, the Nuu-chah-nulth are still living where they have always lived, along the west coast of Vancouver Island. The east coast is the coast along which the cruise liners sail to reach Alaska.

And around Clayoquot Sound they fish, raise their children and move around from village to village (rather than move the villages from site to site as in the past) despite urgent past govenrnmental effort to rid them of their culture by ridding them of their children.

Those measures, as painful as they are, failed. Even the Potlatch has returned. Even the language is returning.

The artifacts in this refurbished gallery were largely taken (in some cases, ‘bought’) around the turn of the nineteenth century when it was thought they might not be needed any more. A bit like the theft of the meteorites from the Innuit, much farther north, who used them as a source of iron.

The Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia ( https://moa.ubc.ca/#menu-what ) in Vancouver is an excellent museum of similar artifacts which also stresses the continuum of culture to this day.

I believe John R. Jewitt was one of their more documented slaves they kept and also were active in slave trading

Nuu-chah-nulth peoples from the Nootka. Sound area traded slaves to the Makah, the Quileute and the Quinault, who in turn traded them on.

Indigenous Slavery on the Northwest Pacific Coast Maxine Berg (November, 2019)

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/ecc/events/scandal/papers/maxine_berg.pdf

I had to google the location. Article does not mention the The American Museum of Natural History is in New York when describing location. I’m in Alaska. For me, New York is not the center of the universe.