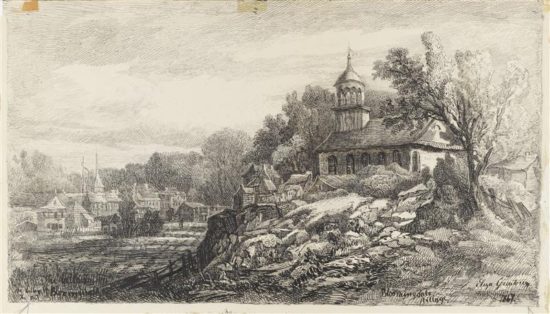

For twenty years the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan from W. 96th to W. 110th Street between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

By Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group

Here is a second post in the series exploring Bloomingdale in Colonial times and after the Revolution. If you missed Part 1, you can find it here.

Colonial New York

New York City’s colonial history provides a context for Bloomingdale’s history before the American Revolution. The City became an economic powerhouse in the 18th Century after Queen Anne’s War ended in 1717. The development of the plantations in the British West Indies to meet the rising demand for sugar drove the New England and the Middle Colonies to become the suppliers of food and other essential supplies for the plantations. New York became, in that time, one of the imperial centers of the British North American empire, the others being Jamaica in the West Indies, and Halifax in Canada.

New York City began to lose its original Dutch cultural heritage as the British economic and cultural practices prevailed. Merchants in New York were drawn into the slave trade as slaves were needed to labor on the farms surrounding the city, as well as to work in building ships, handling cargo, and even the day-to-day work of operating businesses. Some slaves also worked as domestic servants. While we don’t have actual headcounts of enslaved people in Bloomingdale until the 1790 federal census, we can be quite sure that many slaves labored for their masters here. An enslaved population was one of the major features of New York City life in the 18th Century. Another blog post in this series will provide more details about slavery in New York City and the details found about enslaved people in Bloomingdale.

New York City’s aristocracy was one of wealth, not lineage. The merchant princes of colonial New York became the leaders of fashion, politics, intellectual life, and philanthropic projects. They moved to a life of ease and comfort similar to their peers in London. Their personal fortunes were tied-up in real estate and the elegant homes they built in downtown Manhattan. But soon they began establishing “country seats” up the island along both the East and the Hudson Rivers. Along the Boston Post road to Harlem, the Stuyvesants, Beekmans, LeRoys, and Gracies established estates. In what became Greenwich Village, the Delanceys, Bayards, and James Jauncey established themselves. South of Vandewater Heights—in Bloomingdale—the Apthorp, Striker, Delancey and Bayard estates were established by mid-century. The Delanceys named their estate “Little Bloomingdale.”

These estates mixed with the farms that were already well established. Some country seats raised crops for market as well as serving as country retreats. Most estates were what one writer called “theaters for refinement.” Both employed slave labor where the footman who stood behind the master of the house at dinner was a slave, as were the maids and coachman, a colonial version of the gentrified home in England. Gardening and landscaping were important for some, as reflected in the advertisements of the land. Gentlemen were focused on fast horses and fox hunting in Bloomingdale.

Downtown, assembly balls, theater and the Vauxhall filled with waxen figures were features of winter social life. Kings’ College and the New York Society Library were founded. Religious life was important but Bloomingdale did not have enough population to support churches until after the Revolution.

The merchant princes of Bloomingdale were conservative, and many remained loyal to the British Crown when the Revolution came. Their choice would determine the property changes that came after the War.

Early Property Owners Along the Bloomingdale Road

In 1667/68, New York’s Governor Richard Nicolls sold nearly 500 acres on the Upper West Side to Isaac Bedlow, one of the City’s aldermen. In 1688, Bedlow’s widow sold the land to Theunis Idens Van Huysen, often referred to as Theunis Idens or Eidens. He moved his farm from Sapokanikan (Greenwich) to his new property, stretching in some descriptions from 89th Street to 107th Street, encompassing 460 acres. Theunis Eidens’ land was surveyed by the town of New Harlem in 1690, determining that it was in the City’s Out Ward, not the town. In his old age, Theunis Eidens surveyed his 460 acres, dividing it into parcels of 57 ½ acres each, numbered from one to eight, and conveying them to his children, most of whom were daughters. Lot Number 8 went to Rebecca Eidens and her husband Abraham “De La Monontanie,” or Montayne, a Huguenot family, whose farm was east of Morningside Park’s cliff, on the then-called Montayne’s Plain. This name lives on today in the name of the little stream that flows across the northern end of Central Park, Montayne’s Rivulet.

Theunis Eidens Lots Numbered Six and Seven went to his daughter Catalina and her husband George Dyckman. Lots 4 and 5 went to the Eidens son, Eide Van Huyse, Number 3 to daughter Sarah, Number 1 and a portion of Number 2 to their daughter Dinah and her husband Van Vleckeren. Later, in 1762, Charles Apthorp, a merchant originally from Boston, would establish his “country seat” on Eidens’ land, as he came to own Lots 1 to 5.

Eidens’ land was in the City’s Out Ward, the section of Manhattan Island above Wall Street. The Dutch East India Company had divided the downtown section into wards that covered the population living there; later, the British expanded the downtown wards as the population grew. In 1660, the town of New Harlem had been laid out, covering the northern part of the island from 129th Street on the North River —as the Hudson was called —to 74th Street on the East River. The town had surveyed Eidens land to make sure he was not encroaching on the Town.

In 1700, the New York Common Council ordered that land to the north of Theunis Eidens be sold to pay for the new City Hall they planned to build downtown at Wall Street and Nassau Streets, the same building that later served as the Federal Hall for the new capital of the United States. They sold to John Miseroll, who quickly re-sold it to Jacob de Key. In 1732, one of Jacob’s descendants, Thomas de Key, advertised a farm for sale with “a very good stone house.” One record places the house near where Columbia’s Low Library stands today, while another describes it as standing on the south side of West 114th Street, 380 feet east of Tenth Avenue.

De Key’s sale of his farm went to two new owners, Adrian Hoogelandt and Harmon Vandewater. Vandewater took the land to the east of Hoogelandt, leaving him no shoreline on the North River. After his death, Hoogelandt’s land was advertised for sale in 1772 with this description:

That very valuable farm of Adrian Hoghland, late deceased, situated in Bloomingdale, in the outward of the City of New-York, containing 121 acres of choice land, well wooded and watered, with salt meadow sufficient to supply the farm with hay; there is on the premises a large commodious dwelling house and kitchen, a large barn, with stables for horses and cows, with other out-houses, all well covered with shingles, also a large orchard with choice apples, and a very great collection of fruit trees, such as English, and common cherries, pears, peaches, etc. Its vicinity to the City of New-York, together with very extensive and beautiful prospects (commanding a view of new-Harlem, the Sound, Long-Island, New- York, and its Bay, down to the Narrows; and up Hudson’s River for many miles) fitly adapt it for a gentleman’s country seat; and the goodness of soil, for the farmer. The whole will be sold together, or in two parts, as best suits the purchaser.

Another pre-Revolution property owner in Bloomingdale was Johannes Van Beverhoudt who purchased western portions of the land owned by the Eidens’ sons-in-law, de la Montayne and Dyckman. Van Beverhoudt was Dutch, of a family that had settled in the West Indies, on a plantation in St. Croix. Johannes came to New York City with his children and fourth wife, Margaret. They joined the Dutch Reformed Church and, in 1750, the children were recognized as naturalized citizens by the Legislative Council of the Colony. Johannes died in 1751, and Margaret sold his Bloomngdale land to Humphrey Jones. The sale included the stone house which later became the Abbey Hotel, a Bloomingdale landmark. It was placed south of West 102nd Street, west of West End Avenue. Mr. Jones assembled other land as well, including the remaining land George Dyckman owned.

Further south in Bloomingdale, Theunis Eiden’s son, Eyde Van Huysen had sold about 115 acres to Dennis Hicks in 1746. In 1763, Hicks sold his land to Charles Apthorp who established his country seat, building a splendid mansion in 1764 between West 92-93 Streets, west of Columbus Avenue. The construction of the mansion house was in the news in 1764 when George McIntosh, a Scotsman laborer, working there was killed in a quarrel by another workman, Frederick Loudon, a Dutchman, one of the earliest crime reports of the Upper West Side.

In 1764, Apthorp sold the old Eidens homestead and some land to Gerrit Striker, whose holdings were around 96th Street, with the inlet on the Hudson gaining the name Striker’s Bay. Striker built his own house on the bluff where the Eidens home was located. Later, the Striker house became a tavern and then a hotel, one of the popular stops along the Bloomingdale Road. Apthorp also sold to Humphrey Jones the rights to use the old road that went from the cove at 96th Street to Mr. Jones’ property.

South of Apthorp, another portion of Eiden’s land, owned by his daughter Dinah, was sold to Stephen Delancey, who made it his country seat, naming it “Little Bloomingdale.” By 1747, the estate was in the hands of Oliver Delancey, whose family story continued into the years of the Revolutionary War. Delancey built his own house, selling the original house to Apthorp, who transferred it to his brother-in-law James McEvers. McEvers died soon thereafter, and further transfers put the property back in the hands of the Apthorps. It went eventually to Charlotte Apthorp, who married John Cornelius Vanden Heuvel. They built a new house west of the Bloomingdale Road, between 78th and 79th Streets. Their home eventually became Burnham’s, another popular resort on the Bloomingdale Road in the early days of the 19th Century.

In 1774, Apthorp sold a piece of his land opposite the McEvers parcel to Major Robert Bayard, who was married to one of his sisters. He was the agent for the East India Company in New York City.

Further south on the Upper West Side developed in a similar fashion, with the area around 70th Street gaining the name “Harsenville” for Jacob Harsen. Close by was the Somarindyke/Somerindike family’s property which stretched from West 57th to West 70th Streets from the common lands in mid-island to the Hudson River. The Cozine family had property on the mid-town west side as well. Even further south, the Hopper family farmed around 50th Street, west of Seventh Avenue. All of these names proved useful in locating Bloomingdale families on the federal censuses starting in the 1790s.

As more homes were built along the Bloomingdale Road, smaller lanes and roads were developed off the main road, including Apthorp’s Lane (later Jauncey’s) between 93rd and 94th Streets, running through today’s Central Park to the Eastern Post Road, and Harsen’s Lane that ran over to the east side of Manhattan to the Middle Road, an alternative to the Post Road on the east side. Clendening’s Lane ran northeast from the Bloomingdale Road to a point at around 105th Street to Mr. Clendening’s home, built in the early 19th century. Clendening Lane was named “Goodever’s” first, according to the author of the history of St. Michael’s Church; in reviewing property records, however, the property owner appears to be “Goodeve.” The same writer notes “Kemble’s Lane” leading to the former Jones estate, “Striker’s Bay Lane” at 96th Street, “Mott’s Lane” just below 94th Street, and “Livingston’s Lane” at 91st Street.

Sources

Ancestry family histories at www.ancestry.com

Hall, Edward Hagaman “A Brief History of Morningside Park and Vicinity” Twenty First Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Society, 1916

Harrington, Virginia D. “The Place of he Merchant in New York Colonial Life” New York History October 1932, Volume 13 No. 4, pp 366-380

Mott, Hopper Striker The New York of Yesterday: Bloomingdale New York, The Knickerbocker Press 1907

Newspaper databases at www.genealogybank.com and www.newspapers.com

Peters, John Punnett Annals of St. Michael’s, Being The History of St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church, New York for One Hundred Years 1807-1907 New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907

Riker, James Revised History of Harlem New York, New Harlem Publishing Company, 1904

Salwen, Peter Upper Westside Story New York, Abbeville Press, 1989

Stokes, I. N. PhelpsThe Iconography of Manhattan Island (all volumes) New York, Robert H. Dodge, 1928

van Beverhoudt family: https://200inparadise.blogspot.com/2012/06/van-beverhoudts-take-manhattan.html.

Of course the lands of the upper west side, and the rest of Manhattan, really belonged to the natives at that point, since the 30 year fishing license was up.

Right, selling Manhattan for beads is a myth.

Absolutely. The unexamined privilege of the current population is as problematic as the destruction of this once pristine environment.

Did you really write that with a straight face…”the unexamined privilege of the current population”. I don’t know really where to begin. The story described is the story of man all over the world since the beginning of time. It might not have been fair, but that’s what happened. And no you cannot rewrite history because you don’t like it and the current population that you vilify are not responsible for things they had no say in. And by the way, the US is not systemically racist.

Thank you for this!

Love this article, full of fascinating content. Thank you so much! Really appreciate all you bring to the WSR. I’m new to NYC and the UWS, and the history of this small piece of land could fill books.

So interesting, thank you!

A fun fact — a small remnant of Clendenning Lane still exists as a narrow rectangular parcel at the very center of the block bounded by Broadway / Amsterdam / W 102nd St / W 103rd St. This strip of the old lane runs east-west (parallel to 102nd and 103rd Streets). Today, this remnant piece of the lane is occupied by an offshoot of the NYCHA playground, a narrow strip nestled between the backyards of 203-209 W 102nd St and 210 W 103rd St.

This never happened ask any woke history professor in NYC

Many years ago, David Brinkley’s Journal did a show called “Diary of a Tenament”, tracing the journey of the land (Montaigne’s Marsh, bought from the Native Americans for a trifle in the

mid-17th century). It remained in the faamiy for a long time, evolving into the neglected tenements of 1961. Neiher the NBC archives nor the Museum of Broadcasting can find a copy.

Great story…thanks for sharing.