For twenty years the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan from W. 96th to W. 110th Street between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

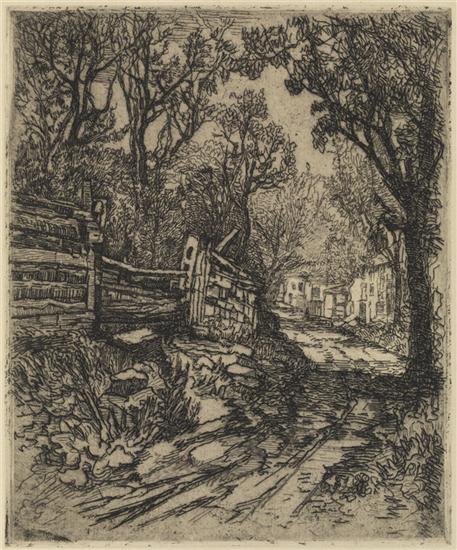

Country Lane Bloomingdale 1870, By Eliza Greatorex. Museum of the City of New York.

By Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group

Introduction

A few months ago, a new website developed by John Jay College caught my attention. Like many institutions of higher education, the College was exploring the link between slavery and the famous man whose name adorns it. One of the resources used was the 1790 federal Census. I looked up Charles Ward Apthorp, whom I had written about previously, one of the colonial property owners in our Bloomingdale neighborhood. He owned eight slaves.

That got me thinking: who were the other people in this census? How was the Bloomingdale neighborhood settled in the era before the Revolution? What was Bloomingdale like after the Revolution and in the early 1900s? I started to dig a bit deeper into the Bloomingdale history, beyond the work of numerous local historians who write about a particular property owner and the history of a mansion house, as I myself had done in writing about Apthorp’s mansion that became Elm Park.

The Bloomingdale Road, authorized in 1703, and laid out in 1707, was key to the area’s development; Bloomingdale became more like a suburb of the city than what we call a neighborhood today. I am especially grateful to my colleague at the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group, Gil Tauber, for his help on the details of the Bloomingdale Road history.

To provide context, I read books and articles about New York City’s colonial history, about how the American Revolution played out here, and the role slavery played in New York City. I also learned about the yellow fever epidemics in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as they played a role in developing our neighborhood, an escape from the crowded streets of downtown Manhattan.

The districts of the 1790-1820 federal censuses covered much more geographical space than just our neighborhood. In order to find just the Bloomingdale residents, I first had to learn about many uptown Manhattan families and where they settled. I used numerous publications such as Riker’s History of Harlem, Stokes’ six-volume Iconography of Manhattan Island, and Mott’s New York of Yesteryear, along with innumerable newspaper clippings. (Those books are listed in the Sources section below.)

The blog posts that follow share what I’ve learned about colonial Bloomingdale and its history in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century.

Along the Bloomingdale Road in the 18th Century

Bloomingdale referred to a district on both the lower and upper West Side of Manhattan Island named by the Dutch as Bloemendahl, a vale of flowers. When the British took over the colony in 1664, changing the name from New Amsterdam to New York, they Anglicized the district’s name. Bloomingdale was never an organized village, like New Harlem. Later, Greenwich Village, although not incorporated, also had more specific boundaries than Bloomingdale which remained somewhat amorphous. Later, it would be defined as a settlement around 100th Street and the Bloomingdale Road. Other neighborhood names developed: Harsenville, in the 70s, was to the south, and Vandewater Heights to the north, where we find Morningside Heights today.

In his Iconography of Manhattan Island, Stokes cites 1688 as the earliest example he could find of the use of the name Bloemendahl, mentioned in a marriage record of the Dutch Reformed Church. Similar names would be given to other early farms: the de Montayne family named their farm near today’s Morningside Park Vredendal or “peaceful dale.”

On June 19, 1703, New York’s Colonial legislature passed an Act naming the Bloomingdale Road as a public road. Later legal actions would cite the fact that it was four rods in breadth as proof that it followed an existing road, since new roads in the Colony were to be six rods. (A rod is 16.5 feet in British measurement.) The existing road was no doubt a Lenape trail, as this was the formation pattern of many Manhattan roads. The Bloomingdale Road would stretch from 14th Street and the Bowery, cross the island in a northwest direction, and end up at the dwelling house of Adrian Hoogelandt at 116th Street, near today’s Riverside Drive. In 1787 legislation about the Road this same place was referred to as Nicholas de Peyster’s barn, the site of Hooglandt’s old house.

In 1707, the Committee responsible for laying out the road declared their work finished. Two of these landowners were “Theunis Eidens” and “Captain Key,” who are mentioned in the next post covering property owners.

In 1751 legislation concerning the Road, it was allowed to have a breadth of two rods. The City also required the appointment of a surveyor of the public road, one who was a resident of the Bloomingdale district. He was in charge of road repairs and had the authority to summon any number of Bloomingdale inhabitants to work for up to six days each year on the Road. If someone produced a cart, spades and pickaxes, that would be counted as three days of labor. Anyone failing to appear would be fined six shillings.

After the Revolution, in 1794, the City’s Common Council decided to “…look into the expediency of continuing the Road until it intersects with the Post Road in Harlem Heights, and to determine if the proprietors through which the Road will pass may be asked of their willingness to give the land for this purpose.” All but two (Molonear and Meyer) were willing, and by 1797 the Council ordered that the new Road should be “put in good order.” Many years later, in 1868, the Bloomingdale Road was officially abandoned after major portions of it had become part of Broadway.

Milestones on the Bloomingdale Road

Colonial roads typically had mile markers to help travelers pinpoint where they were. The 200-mile trip from Boston to New York City along the Boston Post Road would take one week with mile markers helping a weary traveler to gauge the distance. As taverns developed along the road, the mile markers would help locate them. Mile markers were established along the Albany Post Road in 1753, and continued into Manhattan along the Kingsbridge Road. The 12-mile marker was at today’s 212th Street, still in place and incorporated into the wall surrounding Isham Park in Inwood. Other old mile markers are in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York and the New-York Historical Society.

The original mile markers in the City measured the distance from the old City Hall on Wall Street. Later, in 1812, they would be adjusted to measure from the new City Hall, in the park where it stands today.

In 1769, a series of mile markers was established along the Bloomingdale Road, measured from the old City Hall. A new series was put in place in 1813, measured from the new City Hall. In that series, mile number five was at 74th Street, number six at 94th Street, and number seven at 112th Street. These mile markers are helpful in determining the locations of taverns advertised in the newspapers, and for property sales in the Upper West Side area. For instance, in 1785, John Somarindyke advertised a lost cow that had wandered onto his property “near the five mile stone.” Another advertisement, in 1799, described the property at the five mile stone as “one hour from the City.”

The Bloomingdale Road as a Recreational Space

After the Revolution, when George Washington lived in New York City as the capital of the United States, his diary notes long carriage rides taken:

“…long drives in the family coach with Mrs. Washington and the two Custis children on the ‘fourteen miles round’ being covered between breakfast and dinner time. This tour led over the Bloomingdale Road to Harlem Heights thence by a crossroad to Kingsbridge and returning along the Boston Post Road.”

Thus, while many localities boast that “Washington slept here,” our neighborhood can point to the many times President Washington drove through here, as a way of relaxing from the duties of his job. It may have been on one of these drives when he expressed the opinion that the new capital buildings might be located on the bluff overlooking the Hudson, near the location of the Claremont estate at 123rd Street.

By the nineteenth century, while Bloomingdale remained rural, before Central Park was developed, the Road up the west side provided pleasure to those who owned horses and carriages. Mr. Mott, in his book about Bloomingdale, writes,

“the country on either side of it was so fresh and rural, the houses so charming whether they were the villas of millionaires or two-story cottages of dwellers with small revenues, and the glimpse of the Hudson sometimes at the foot of a narrow lane, where the water was but a point of lightness closing the vista, sometimes a broad expanse showing a large and noble view of the grand river.”

Farming in Bloomingdale

The land in Bloomingdale was farmland, growing the crops needed to feed the city’s residents on the southernmost tip of the island. Food grown in New York also fed the slaves in the Caribbean islands, as the land there was more valuable for growing sugar cane. The Dutch had introduced wheat to the colony; native people already grew beans, squash, and other domestic plants. Initially, cattle, sheep, and swine had to be imported. The Village of Harlem to the north and east of Bloomingdale grew wheat, maize, buckwheat, and flax. By the late 18th Century, grain production had shifted upstate, while those with farms close to the city produced the highly perishable products that could be brought to market quickly and easily. Manhattan farming concentrated on fruits, vegetables, and milk.

My research about 18th century Bloomingdale did not reveal any specific details of growing crops locally and taking them to market, although the early owners of land here were presumed to be farming their land. By 1728, there were five markets in downtown Manhattan along the East River waterfront. Many crops, from Brooklyn, Queens and uptown Manhattan, were moved to their markets by water. When one early landowner purchased land that included the shoreline at West 96th Street, an owner further north made sure to purchase the right to use the road that connected his estate to this shore point, suggesting that access to the water was important, perhaps for moving food supplies downtown.

Later in the 18th Century, when merchants began to purchase Bloomingdale land as their “country seat”, it appears that farming the land continued, but I found no details of a relationship with an overseer, or tenant leases for a portion of the land. Tenancy on farmland was well-established in colonial New York, as the great manorial estates north of the city belonging to the Livingstons and Van Rensselaers were farmed by tenant farmers. As I scanned the federal censuses—finding many unknown names—it may be that they were tenant farmers on the Bloomingdale estates.

Certain writers have mentioned growing tobacco in Bloomingdale, and then linking that fact to slavery. There may well have been tobacco growing there, just as there was further east in Harlem. However, slavery was pervasive in New York throughout the 18th Century and enslaved people worked on many of the farms and estates of Bloomingdale, as will be discussed further on.

Advertisements for land in Bloomingdale provide the most specific examples of farming during this era. The Apthorp estate, established in 1764, was described in an advertisement in 1780 as including many features besides the elegant mansion house:

“Also a two story brick house for an overseer and servants, a wash house, cyder house and mill, corn crib, a pidgeon (sic) house, well-stocked, a very large barn, and hovels for cattle, large stables and coach houses, and very other convenience… excellent fruit trees.” The ad refers to the estate as being “very profitable” for a gentleman, suggesting that economic activity would be occurring.

A 1782 advertisement reads:

Between fifty and sixty acres of exceedingly good land, lying at Bloomingdale, in the island of New-York, on which is a good Dutch barn, well-floored, with stables, cow stalls, hog pen …The Farm is well-wooded and watered, a great quantity of fruit trees of all sorts, above one hundred locust trees of a very large size,a nd produces near fifty loads of hay yearly. There are also eight acres of Grain now in the ground.

Finally, an 1808 advertisement for a House and Farm, situated at Bloomingdale, about 20 rods north of the six mile stone, includes:

On the Farm are more than fifty cherry trees of the best kinds, more than one hundred peach trees of excellent sorts, a great number of plumb (sic), quince and pear trees, and a good-sized apple orchard, all in full bearing. The Garden is well-stocked with currants, gooseberries, raspberries, and strawberries, with asparagus beds. The Farm consists of 25 acres, which affords pasturage for six cows, besides producing annually about 5 tons of hay.

Colonial Bloomingdale property owners will be covered in my next post.

This post was originally published on the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group website and is reprinted with permission.

Sources

Riker, James Revised History of Harlem New York, New Harlem Publishing Company, 1904

Mott, Hopper Striker The New York of Yesterday: Bloomingdale New York, The Knickerbocker Press 1908

Newspaper articles from www.genealogybank.com and www.newspapers.com

The Green Bag, a Magazine for Lawyers Volume XXIII covering 1911, The Riverdale Press, Brookline, Boston, Massachusetts. Article “Bradley vs. Crane” regarding the Bloomingdale Road history

Koke, Richard J. “Milestones Along the Old Highways of New York City.” New York Historical Society Quarterly Volume XXXIV, Number 3

Burrows, Edwin G., Mike Wallace, et al Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 New York, Oxford University Press 1999.

Very interesting and thorough.

This filled in many gaps in the history of my 40+ year neighborhood. Thanks for the deep research.

I enjoyed this and look forward to the next installment

The history of our city is of endless fascination to me. Thank you, Ms. Tice, for some very interesting reading. Do you suppose that the locust trees mentioned in the 1782 advertisement our ubiquitous honey locusts?

“the glimpse of the Hudson sometimes at the foot of a narrow lane, where the water was but a point of lightness closing the vista, sometimes a broad expanse showing a large and noble view of the grand river.”

That hasn’t changed much; it’s my daily experience, but seeing more trees these days. But a call to the water.

Fantastically well-written. Thank you so much!!

The Hudson valley has an an endemic variety of black locust trees called Ship mast locust. I do not think they were used for masts but, they tend to grow tall and with an upright form. They have clumps of fragrant white flowers in early June. The wood has a high silica content and is rot resistant and was valuable for fencing.