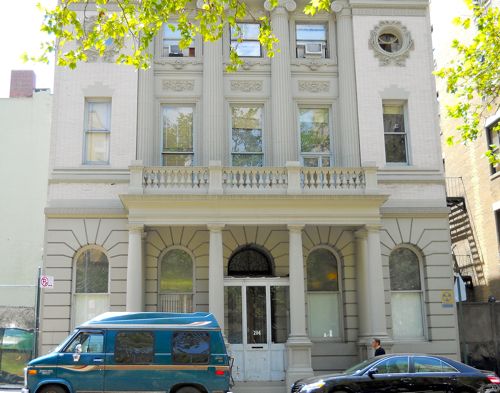

For more than 20 years I walked past the neoclassical building at 206 West 100th Street, just west of Amsterdam Avenue, curious about both its past and its present. It remained just one more of those tantalizing New York mysteries that fascinate me until I did some research into its history. My research led me, happily, to an encounter with a most interesting, most inspiring West sider named Oksana Radysh.

To begin at the beginning: The building which had so captured my interest was built in 1898 as the first and only building built and commissioned by the New York Free Circulating Library, a precursor of the New York Public Library system. The circulating libraries , incorporated in 1880, were designed to provide “moral and intellectual elevation to the masses.” Before this, libraries had been primarily for the use of scholars. Among the supporters of this populist movement were Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt and other notable philanthropists of late nineteenth century New York. The 100th Street building was named the Bloomingdale Branch after the 18th and 19th century village that was once centered around 100th Street but virtually disappeared with the urbanization of the neighborhood that followed the arrival of the 9th Avenue El in 1879. The core of the library’s collection came from the 3,000 volume parish library of St. Michael’s Episcopal church, just around the corner, that had been rapidly running out of space for its books.

James Brown Lord (1859-1902) was chosen as the architect of the building. Lord, who like most architects of the time was a member of an influential and wealthy New York banking family, designed many private houses for family friends in Yonkers, Bar Harbor, Maine, Tuxedo Park and here in the city. Lord was the designer, with Stanford White and his firm, of the row houses on 138th Street now called “Striver’s Row”. His most prominent work is probably the Appellate Division Courthouse on Madison Square. Lord’s library building, landmarked in 1989, has remained virtually unchanged since it was built and is the prototype design for many other urban branch libraries.

When the Circulating Library and the New York Public Library merged, the building became the Bloomingdale branch of the new system which remained in the 201 West 100th building until, in 1960, it moved to a new facility across Amsterdam Avenue at 150 West 100th Street.

Enter Oksana Radysh, or more accurately, her father, Volodymyr Mijakovs’kyj. Ms. Radysh’s father was a well-known Ukrainian scholar who dedicated his life to documenting the history of the Ukrainian emigration in North America and other parts of the world. To do this he co-founded the Ukrainian Free Academy of Arts and Science in the American Zone of occupied Germany in 1945. Five years later he transferred the Academy’s archives to the U.S. With perseverance and devotion to his cause, he managed to gather together many valuable collections of documents that encompass all aspects of the Ukrainian emigration experience: press, literature, science, the arts. Once established in the U. S., the Academy became officially incorporated as the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.

In 1960, when the city put the former Bloomingdale library building up for sale, Mijakovs’kyj, who lived nearby, saw an incredible opportunity. The city was asking just $47,500 for the building but the Academy had nowhere near that amount of money in its account. Mijakovs’kyj put the word out that the building was available and many interested scholars and professors pooled their resources, making it possible to buy the building.

After researching the origins of the building, I wanted to see what it looked like inside and what exactly this rather esoteric sounding Academy was all about. I stopped by one day and was told that the person I should talk to was Oksana Radysh and that I should call to make an appointment. When I did, Ms. Radysh seemed eager to have me come by. I made a date for the following day.

When I rang the bell at the Academy, a diminutive woman came to the door and welcomed me with a warm smile. I reached out to shake her hand and she told me, in her soft-spoken way, that there is a superstition in the Ukraine that prohibits shaking hands before one enters a building—once over the threshold she took my hand. Oksana Radysh is 91 years old; she is small and fragile-looking and has bright, intelligent eyes that belie her years. She works at the Academy, continuing the work of her father, seven days a week, 12 hours a day, often walking home a few blocks away at midnight. Her friends worry about her but she insists that this is exactly what she wants to be doing.

The inside of the Academy is dimly lit — Ms. Radysh doesn’t like bright light. What had been the reading room of the library is a large open space where the Academy offers Sunday lectures in Ukrainian — “we like to keep our language alive” —and the occasional concert. I asked her why there were two pianos in the room: “Because one doesn’t work and the other was just donated to us by the sister of a Ukrainian pianist who died recently. It needs tuning but we can’t afford that right now. “

There is an office area in the front of the ground floor room with some modern equipment—a computer and copy machines– but Ms. Radysh does not use the computer (“I am not acquainted with the computer”). She has someone who comes in during the week to do whatever needs to be done via the internet. The building has three floors. On the third floor there is an apartment for the caretakers of the building, a husband (an engineer) and a wife (a librarian) who recently emigrated from the Ukraine.

On the second floor are the archives which are tended to by a librarian who comes when she is needed.

Ms. Radysh’s domain is the first floor where she oversees dozens of mismatched, ancient file cabinets filled with carefully labeled folders on Ukrainian artists — catalogs, letters, newspaper articles — about 400 artists in all. The Academy also has a copy of every single issue of the newspaper Svoboda (which means Freedom in Ukrainian) since 1914! Around the room there are some lovely examples of Ukrainian folk art—a beautiful patterned rug, several ceramic bowls and pitchers and small sculptures.

Along one wall is a double row of black and white photographs of nationalist scholars. Ms. Radysh explained that all of the men depicted in the top row of photos had been either arrested or shot to death in the Ukraine.

But one of the most amazing discoveries of my visit was what was hanging on the back wall of the main room and the wall just to the right of the entrance. This is where Ms. Radysh has displayed her own husband’s oil paintings and they are spectacular. Ms Radysh married Miroslav Stephan Radysh in a displaced persons camp; he had been the chief designer at the Lviv Theater of Opera and Ballet. (Lviv was a major cultural center of the Ukraine before World War II). They came to the U.S together in 1950 and he died just six years later at 46. His paintings include landscapes of the Carpathian mountains, a striking self portrait, as well as scenes of New York.

Ms. Radysh pointed out one painting of a courtyard — criss-crossed with laundry hung out to dry — that depicts the building in the Bronx where the Radysh family first lived when they came to this country. To honor the 100th anniversary of her husband’s birth last year, Ms. Radysh had postcard sized reproductions of some of his paintings made—she gave me a set as a gift. They are beautiful.

One of the projects that Ms. Radysh is working on now is a series of lectures to honor the 150th anniversary of the death of Taras Shevchenko, probably the most famous Ukrainian poet and artist, who began life as a serf and is credited with being the founder of modern Ukrainian literature. An interesting aside: Taras Shevchenko Place, a small walk-through between East Sixth Street and East Seventh Streets, was named in the writer’s honor in 1978; before that it had been known as Hall Place for an otherwise unknown New Yorker who had once owned the land.

Trying to keep up the landmarked building and her beloved academy seems to be a challenge for Ms. Radysh but she is certainly bound and determine to succeed. As I left, after two wonderful hours in her company, I promised to return and in the meantime to tell other Westsiders about the mostly unsung work that she does and the cause that has kept her so engaged and involved all these years.

Marjorie Cohen has lived on the Upper West Side since the mid 60’s. A big fan of the neighborhood, Marjorie played an active part in the life of the West Side as Executive Director of the Westside Crime Prevention Program/Safe Haven for more than 20 years. Now, with WCPP’s mission accomplished, Marjorie is concentrating on writing and editing. She is the author of seven travel books including the Whole World Handbook and Great Vacations with Your Kids and has edited books on subjects from criminal justice to psychology. Her recent credits include articles on West Side landmarks for amNewYork. She is a West Side Rag columnist.

I would like to express my gratitude to

Ms. Marjorie Cohen for revealing to general

public, what is hidden behind the walls of this historical building. Ms.Oksana Ratych,

91 years young, gives her life and devotion

to this Ukrainian Institution !

Thank You Marjorie Cohen for sharing this inside look at not only a historic landmark building and its history but the cause Oksana has undertaken to documenting such a major component to New York’s emigrant community of the Post World War II era.