This is the third article in our History Beat series — columns inspired by materials about the Upper West Side from the library of the New-York Historical Society. This article references items from the library’s newspaper files. Many thanks to the librarians at the N-YHS for their help and encouragement.

Let’s take a look back to the Upper West Side of the 1930’s and a building constructed just as the Great Depression began. For decades, it was part of a delightful and innovative business experiment, and on one day in the middle of the summer of 1933 it was the scene of a strange and tragic series of events.

The building is the one that stands on the southeast corner of 104th Street and Broadway. Built in 1930 as a Horn & Hardart Automat/Cafeteria, it is a wonderful example of an art deco commercial structure of the period. Although at the moment the building is marred by the storefront and signage of a Rite Aid, it has been declared a landmark. And, thanks to the perseverance of a community resident/preservationist, the Rite Aid powers-that-be were convinced to cover, not destroy, the first floor of the building when they leased it. At some point, it is hoped, the building will be “unwrapped” and we will be able to see it in all its 1930’s glory.

The 104th Street Horn & Hardart was designed by the firm of F.P. Platt and Brother (F.P. was Frederick Putnam Platt and his brother was Charles Carsten Platt) who had worked on H&H buildings since 1916. By the time the brothers got to the one on the Upper West Side, they had firmly established the commercial image of the chain with its large signature windows that made it possible for patrons to see out and for passers-by to see in. The Platt’s H&H buildings were an excellent and early example of “branding”. Because of their work with H&H, the brothers received commissions from many large New York firms and institutions — the New York Athletic Club, Con Edison (buildings and power plants), Metropolitan Life Insurance, New York University and more.

A “Democratic” American Innovation with Origins in Germany

The story of H&H is a wonderful, truly American tale. The automat is considered such a quintessentially New York institution, but in fact it was established in 1902 in Philadelphia. Horn was the son of the founder of a surgical company and Hardart was an immigrant from Bavaria who, when he arrived in New Orleans in the mid 1800’s, began to work at a lunch counter brewing French-drip method coffee.

When Horn moved to Philadelphia he put an ad in the paper for a partner in a restaurant venture and Hardart answered it. The two opened a small luncheonette where their New Orleans-style coffee drew crowds. As Horn is quoted: “There’s no trick to selling a poor item cheaply; the real trick is to sell a good item cheaply.” And that’s what the partners set out to do when they set up their own version of a German prototype of a waiterless restaurant or “automatic”.

Ten years later the pair decided to take their automat concept to New York City and in 1912 opened their first in Times Square between 45th and 46th Street. They had chosen the perfect spot as a writer at the time noted: “Besides the after-theater crowd, the boardinghouses and cheap hotels that lined the side streets assured it a three-meal-a-day clientele of theater hands, clerks and blue-collar workers. Restless New Yorkers, their numbers swelled by almost a million immigrants in the preceding decade, stayed up late, moved fast and positively enjoyed buying from machines.”

The automat, in spite of its German origins, is thought of as a uniquely American-type institution. It was a truly democratic place, popular with celebrities, women who worked, artists, white collar and blue collar types, rich and poor. They put in a nickel and out came a main dish, a bowl of soup, a piece of pie. For less than 50 cents they could have a filling and tasty three course meal. (If you want to recreate the automat eating experience at home, take a look at The Automat, written by Lorraine B. Diehl and Marianne Hardart– a great granddaughter. It has H&H’s recipes for baked beans, macaroni and cheese, chicken pot pie and more.)

In the beginning the automat was the perfect place for people who had lived in boardinghouses where meals had once been provided but were now living in places converted into rooming houses without kitchens.

When the H&H was built on the Upper West Side there were 42 other company automat-cafeterias throughout the city. It remained in this spot until 1953. What makes the mostly limestone building recognizable immediately as an H&H structure is it’s huge entrance portal with show windows on either side, although as mentioned above the Rite Aid storefront now obscures much of what was once a grand entrance. But what is most appealing to architecture enthusiasts is still visible at the top of the building– the terra-cotta panels with stylized floral motifs and zig zag patterns in green, blue and tan glazed terra cotta. What makes this a particularly interesting trim are its accents of gold lustered glaze, a glaze found only on two other buildings still standing in New York.

Broadway and 104th Street was a perfect spot for an automat-cafeteria in the 30’s. The subway stop was nearby, there were several large apartment buildings within a few blocks, residential hotels without kitchens – one of these, the Regent, was right across the street — and several movie theaters including the Midtown, the Essex and the Olympia nearby. This is the spot where Henry Jellinek and Lillian Rosenfelt came on what was to be a fateful July morning.

A Horn & Hardart Mystery

Jellinek and Rosenfelt went to this H&H on Wednesday, July 26, 1933 separately and died just hours apart. And no, it had nothing at all to do with the H&H food.

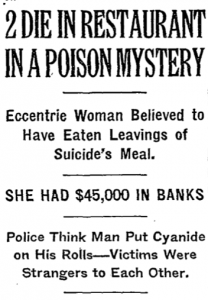

The incident was reported in The Herald Tribune, The New York Times and The Sun on the following morning. (On the first page of The Sun of that day was an article declaring that cigarettes had gone up to 12 cents a pack and an advertisement for the Arnold Constable department store featuring a “dated shirt”– a man’s dress shirt guaranteed for one year that cost $1, with two collars, $1.25.)

It seems that Jellinek, an auto mechanic who had his own business on Tenth Avenue, went into the H&H determined to commit suicide. He brought in two rolls from an outside source, sat at a table, took a bite of one of the rolls, immediately took sick and went to the restaurant’s bathroom. A little while later, Lillian Rosenfelt, an eccentric known locally as Lillian Fields, went into the restaurant and before long also became ill. When a customer called an ambulance from Knickerbocker Hospital (then located on Convent Avenue) a Dr. Wandik arrived. While Wandik was attempting to treat Rosenfelt, a man ran up from the basement bathroom to say that he had found Mr. Jellinek lying on the floor. At this point, someone went to get Dr. Harry March, a former physician to the New York Giants football team, who lived around the corner at 236 West 103rd Street. In spite of the efforts of the two doctors, Jellinek died on the spot and Rosenfelt died a few hours later at the hospital.

An autopsy was performed by a Dr. Gonzales who announced that they had both died of cyanide poisoning. The medical examiner confessed that he didn’t “know what to make of it.”

The investigation that followed revealed that Jellinek had been ill for weeks and depressed about business—not surprising in 1930’s New York. His wife and son, an 18 year old student at NYU, were “prostrate and would tell the police nothing” when they visited their apartment on 170th Street.

The investigation that followed revealed that Jellinek had been ill for weeks and depressed about business—not surprising in 1930’s New York. His wife and son, an 18 year old student at NYU, were “prostrate and would tell the police nothing” when they visited their apartment on 170th Street.

It was discovered that Rosenfelt, the daughter of a real estate operator in New York and Boston, had been living down the block from H&H in a dingy cellar room filled with junk. In the junk, police found five bank books with a total of $45,000 in savings.

When the story was pieced together, it was determined that Jellinek and Rosenfelt did not know each other. In fact, Rosenfelt’s estranged sister said that it was “preposterous” to think that her sister might have been a friend of Jellinek’s because she was a “man-hater.”

The police theorized that Jellinek, determined to commit suicide, brought in two rolls with cyanide on them. He ate half of one. Rosenfelt then passed the table, saw the rolls, put one in her bag for later and ate the other “thinking she would save a nickel on her breakfast.”

From 1953 to now

After H&H closed, the building had $10,000 of alterations done, the counters and stairs to the mezzanine were removed and a full floor was created on what was the mezzanine. The second and third stories were converted to office space. For a short time the Bloomingdale Branch of the library’s children’s room was here, then a succession of other enterprises including a number of supermarkets, a coffee shop, a pizzeria and finally Rite Aid rented the first floor.

Over the years, the upper floors have been rented by a Mr. Universe Health Studio, a secretarial school, an art gallery, accounting and law offices and El Taller, a nonprofit arts and education center that is still there. The for-sale sign that was on the building until recenly is no longer there, so hopefully it has been sold to someone who will unwrap its first floor. That way we can get an idea of how it looked to West Siders 82 years ago.

To read the other articles in this series, click here.

Margery – another wonderful article and rather nostalgic for me, because my mother used to take me to H&H. It was such a great adventure.

Thank you very much.

Terrific and fun! Thanks!

I was the Editor of WISDOMS CHILD.

Love the history stuff!!!

Best, Neal

Neil Hurwitz:

I wrote for Wisdom’s Child during the fall of 1976. I don’t remember you, but I remember Deborah (sp?) Wollens. No offense, but I’m still rather pissed off about Wisdom’s Child’s policy of not paying its freelancers/contributors. I was out of school and wanted experience–I didn’t get one thin dime. Thankfully, I found someplace better within a few months.

I LOVE HISTORY!!!! I LOVE HISTORY!!! Thank you for the article….

Between 1937 and it’s closing I had hundreds & hundreds

of meals at that Automat. After school I shined shoes in

front for a lot of customers exiting the subway kiosk there.

I didn’t see a mention of the Edison movie theater, which was

adjacent to the Automat towards 103rd St. It has been 60

years since I last ate the baked beans…but my memory can

still conjure up the unique savory taste, Thanks for the

memories.

I enjoyed the H&H near 45th Street in the 70’s when I was taking my daughters to dance class at New Dance Group Studio. It must have been the last one in the city as well as the first.

While I’ve always enjoyed the H&H facade and the fact that it was landmarked, I am deeply aggrieved at the closing of Rite Aid. Since the onset of Parkinson’s this local store is one of the few I can walk to, buy a few necessities, and the pharmacists who supply my prescriptions are like family friends. Now what! 110th Street may not seem far to some.

Equally bad is the loss of the neighborhood, no, city resource on the top floor, El Taller, offering Spanish lessons, dance classes, art shows, and many, many other invaluable contributions to New York culture. My understanding is that the rent tripled, as did that of Rite Aid, which may or may not have anything to do with the sale of the building.

Rite Aid to be replaced by a walk in medical center. Who will pay for the remodeling. Will we be stuck with another landmarked eyesore like the Orpheum?

Thanks for letting me vent.

It’s nice to see a comment I made in March of 2013 used

again referencing what might have been the most innovated

restaurant chain in the country. The food was GREAT, the

prices affordable for everyone. The last time I mentioned the

baked beans (which I can still taste), now I want to tell you

about the orange glazed cupcake that I still long for.

What’s interesting about this article is that people were very much concerned about their finances then because the 30’s were extremely hard times for everyone. It seemed to have become a sickness to save every single penny no matter how much money you had because the fear of being poor made many mentally unstable. I remember as a child hearing about old people living in poverty with Millions of dollars in the bank because they lived during a time when nothing was guaranteed. But whats even more interesting is that people today live far beyond their means because they think the money will always be there. In todays world the mental illness has been reversed.

Thoughtful, thorough & enlightening. It’s a pleasure to read each & every one of Margery’s entries. This is local history at its best. Many thanks for all the hard work entailed.

Bill Keelty